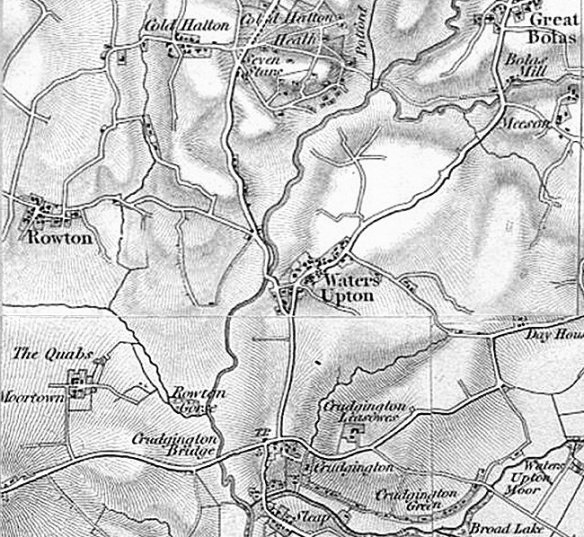

The Rev John Thomas Halke was Curate of the parish of Waters Upton from 1859 until 1867. When he departed the village, John took with him a gift of silverware from the parishioners, along with their best wishes. He left behind him a long-lasting monument to his endeavours: a newly-built church which, with a few modifications, still stands today.

The ministry was in the blood of the Halke family. Richard Halke of Kent was educated at Corpus Christi, Cambridge, and ordained as Deacon in 1766 then as Priest in 1768. He served thereafter as Curate and Vicar, mainly in Kent, until his death at the age of 70 in 1813. Richard’s sons Charles (born abt. 1784) and James (born 1787 at Faversham, Kent) were also educated at Cambridge. Charles passed away aged about 20 in 1804, but James went on to follow in his father’s footsteps. After holding several curacies in Kent, in 1831 he became the Vicar of Weston-by-Welland in Northamptonshire. It was there that Richard’s son John Thomas Halke was born on 7 May 1832.

Commencing his education at Uppingham School, John was then admitted to St John’s College, Cambridge, in 1851. He obtained his LL.B. in 1858, by which time he had lost his father (in 1853) and been ordained as Deacon (in 1856), appointed Curate of Atcham in Shropshire (also in 1856; the church of Atcham St Aeta is pictured below) and ordained as Priest (in 1857).

John set up home in Shropshire with his widowed mother Mary (the marriage of James Halke and Mary Starr had taken place at Canterbury, Kent, in 1817). Something of John’s character, and of the esteem in which he and his mother were held, can be gauged from the following report published in the Shrewsbury Chronicle of 7 August 1857:

On Wednesday week last, an evening of great pleasure was spent at Chilton, through the kindness of the Rev. J. T. Halke, curate of Atcham, he having invited the wives of the labourers, and other working classes of the parish, to a tea-drinking; also the children from the Union, in all numbering about 230. They began to assemble at about half-past three o’clock, and after having enjoyed a most excellent tea, dancing was commenced by the elder party, and bag races and other games for the children. The amusements drew to a close at 9 o’clock, and after having sung God Save the Queen, and given three cheers for the Rev. J. T. Halke, and the mother of the rev. gentleman, they all separated with many good wishes, and hearts full of gratitude to their kind benefactor.

John’s time at Atcham was short but sweet. His “general kindness the poor and needy, attention the sick and dying, and his friendly visits to the infant school, rendered him a general favourite in the parish”, but in the summer of 1859 he was appointed to the curacy of Waters Upton. The first baptism John performed at his new church took place on 19 June that year. He did however return to Atcham later in 1859 for a final farewell from his faithful flock. The Wellington Journal of 8 October 1859 carried the following notice:

Presentation.—The Rev. J. T. Halke having resigned the curacy Atcham for that of Waters Upton, the parishioners determined to present him with a testimonial on his leaving them, he having gained great respect by the zealous and untiring manner in which he performed the office of minister amongst them; they accordingly assembled on Friday week, at the Berwick Arms Hotel, and read a very feeling address. Mr. Halke replied suitably. The testimonial consisted of a tea service which was very chaste and beautiful (furnished by Mr. Nightingale, of Shrewsbury), and bore the following very appropriate inscription:—“Presented to the Rev. John Thomas Halke by the parishioners of Atcham, as a reward of their sincere respect and affectionate regard. September, 1859.” The obverse side bore the family arms and motto.

At Waters Upton, John Halke and his mother continued in the same spirit which had endeared them to the inhabitants of Atcham. In 1860 their names headed a subscription list set up to pay for the children of the Industrial School near Waters Upton to have a day out on the Wrekin. John also accompanied the party, and with others he “contributed not a little to heighten the enjoyment of the children by participating with them in their amusements”.

Preaching, of course, also formed part of John’s duties, and it was not confined to the church in Waters Upton. In the Autumn of 1861, for example, at the Harvest Festival held at Uffington in Shropshire, “an admirable sermon, both in matter and delivery, was preached by the Rev. J. T. Halke, of Waters Upton, from Jeremiah v. part of the 24th verse: ‘He reserveth unto us the appointed weeks of the harvest.’”

A full picture of John Halke’s duties at Waters Upton is difficult to paint, as the burial and marriage registers covering his curacy are still in use and not available to peruse. However, as with his sermons, his performance of the rites and ceremonies of the church was also carried out in other parishes from time to time. To give just one example, in 1862 Edward Ryley of Little Drayton and Mary Ellen Atcherley of Ercall Magna were married at High Ercall by “John T Halke, Curate”.

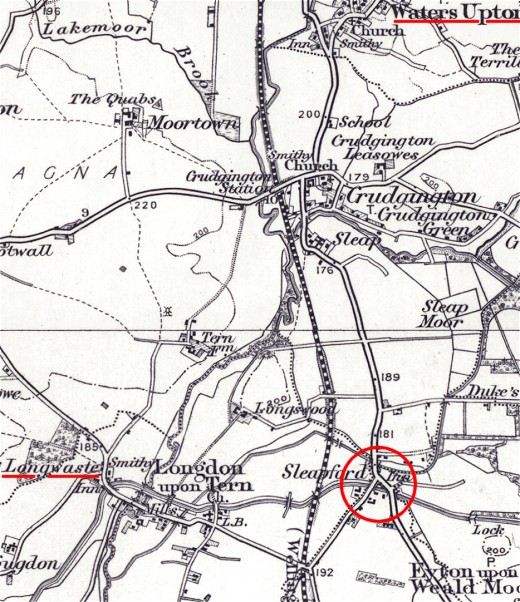

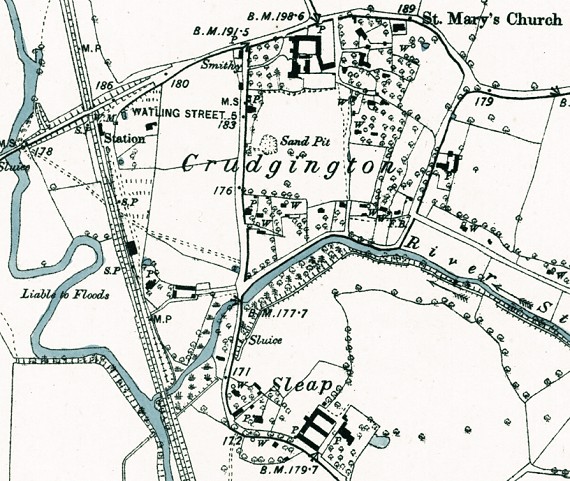

The only marriage that I know of which was conducted at Waters Upton during John’s curacy was quite possibly the last one to be held there before the existing church was demolished. John Higgins Esquire of Lubstree Park and Elizabeth Groucock of Meeson in the parish of Great Bolas were wed on 9 June 1864. By that time it had already been announced that the money for rebuilding Waters Upton church “on an enlarged plan” was ready.

In July and August 1864, notices appeared in Shropshire and Staffordshire newspapers calling first for “about eight or ten good masons” and later, “six or eight good stonemasons” to work on Waters Upton Church. One of the stonemasons who responded to these advertisements was a man by the name of Thomas Parry, who had an unfortunate experience when he looked for lodgings in Wellington (see 1864: A charge of felony in Crime, elsewhere on this website).

A letter from John Halke appealing for contributions towards the cost of the project, no doubt written in 1864, was published in The Herts Guardian in May 1865 (by which time, although funds were still needed, work was almost complete). It sets out the reasons why the rebuilding of Waters Upton church was considered necessary:

Application has been made for aid towards rebuilding the church of Waters Upton, Salop. The curate writes in behalf of what he styles a work of necessity, and states:—“The living has been sequestered for many years, and I have consequently, sole charge of the parish. The population is not very large, but, as some of the poor inhabitants, of the two adjoining hamlets, are in the habit of attending this church, (all of them being from two to four miles distant from their own), it is quite too small for the congregations, and is much out of repair, and being besides, a most unsightly structure, it is thought advisable to take it down, and rebuild it on a larger scale, at a cost of about £1500. This most desirable object can only be obtained by subscriptions. I shall receive therefore, with much gratitude, the smallest contribution, even a shilling in stamps.—Yours very respectfully, John T. Halke.—Any remittance by post order may be made payable on the Wellington office to Rev. John T. Halke, Waters Upton, Salop.”—The list of subscriptions enclosed amounts to about £800, so that above half the required sum is promised. The Bishop of Lichfield gives £10; probably some of our opulent readers may be disposed to aid.

On 23 May 1865, John Halke’s dream of a new church for Waters Upton became reality (see above for a modern-day photo of the building). The Staffordshire Advertiser of 27 May reported as follows:

The parish church St. Michael’s, Waters Upton, Salop, was re-opened on Tuesday, and consecrated by the Right Rev. the Lord Bishop of the Dlocese. The old building had long been in a state of complete dilapidation and was quite unfit for the purposes of public worship. When the Rev. J. T. Halke came to Waters Upton, six years ago, he wished to remedy this state and received such promise of support that the tottering ruin was levelled to the ground, and a very handsome and commodious new building erected by Mr. Cobb, of Newport, at a cost of about £1,800. At the conclusion of divine service in the morning, the burial ground was consecrated, after which the company sat down in an adjoining field to a cold collation. Collections took place after each service, and a handsome sum was realised towards paying off the portion of debt which still remains on the building.

The Mr Cobb who erected the church was most likely John Francis Cobb, son of the late John Cobb, architect and builder, of Chetwynd End near Newport, Shropshire. The design of the new place of worship however was Essex-born architect George Edmund Street, who already had a number of ecclesiastical buildings large and small to his credit. Described in modern times as a “small, cheap but carefully detailed church”, St Michael’s was constructed in Early English style from red sandstone ashlar, with a tiled roof, and an octagonal bellcote (or bell-turret), corbelled over the West gable. It is now a Grade II listed building.

John Thomas Halke was not destined to enjoy the fruits of his labours at Waters Upton for very long. He had been undertaking the role of Curate for the Rector of the parish. But in August 1865 it was announced that “The Lord Chancellor’s rectory of Waters Upton, near Wellington, in this county, has become vacant by the death of the Rev. Richard Corfield, M.A. formerly of Clare College, Cambridge, who was presented by Lord Chancellor Eldon in 1822.” At the end of the following year, this report appeared in the Shrewsbury Chronicle:

Testimonial to Mrs. Halke and the Rev. J. T Halke.—The living of this parish has recently been purchased (under Lord Westbury’s Act) by John Taylor, Esq., and presented to his nephew, the Rev. John Bayley Davies. The Rev. J. T. Halke has had the sole charge of the parish for the last eight years, and during that time he has performed his duties most faithfully and zealously, administering in every way to the temporal and spiritual wants of the poor, and being at all times profuse in his charities to them. When he entered the parish the church was an old, ugly structure, and through his exertions a new church, of very beautiful design, has been erected by public subscription. When it was made known that he was about leaving this parish to remove to [Withington], a subscription was at once commenced, by general consent, and to which every parishioner, without exception, most willingly contributed—even the poorest gave their mite. A sufficient sum was soon collected to purchase a handsome and useful present of the following articles, all in silver:—Two handsome sugar vases, 12 fish knives and forks, asparagus tongs, and large fish fork. These were presented to Mr. Halke and his mother, Mrs. Halke, who had given such valuable and kindly aid in his efforts for the good of the people. It may not be out of place to give the pleasing reply which was received by each contributor:—“Waters Upton Rectory, Dec. 12th, 1866.

“My dear Parishioners and Friends,—I beg to offer you my own and my mother’s heartfelt thanks for the beautiful and costly token of regard and esteem which we have just received from you. We shall value it as long as we live, as a testimony of your liberality, and still more for the kindly feeling with which it is given. The eight years of our abode at Waters Upton have been among the happiest of our lives; we leave it with deep regret and shall ever remember it with the warmest affection. For a time, at least, we shall have the satisfaction of regular intercourse, and wherever our future lot may be cast, we shall ever look back with pleasure to the period of our residence here. Dear Parishioners and Friends, I once more thank you from my heart for your beautiful present, and for all your kindness towards me.—Believe me, to be your very sincere Friend and Pastor,

“John T. Halke”

John began performing baptisms at Withington on 28 October 1866, but continued his curacy at Waters Upton into 1867, conducting his last baptism there on 24 February that year. Wednesday 7 March 1867 was “appointed by the Lord Bishop of this Diocese to be held as a day of prayer and humiliation on account of the cattle plague” and on the morning of that day John “preached from Jeremiah vii. 3.” at Waters Upton. If this was not his final sermon at Waters Upton, it was certainly one of the last that he preached there.

On 30 January 1873, at St Cross in Winchester, “the Rev. John T. Halke, Vicar of Withington, Salop” was married to “Lucy, eldest daughter of the late Richard Meredith, Esq., of Bishop’s Castle.” The couple had four children at Withington, and John passed away there on 8 September 1915 at the age of 83. A stained glass window, in memory of the Rev. John Thomas Halke LL.B. curate in charge (1859 to 1867), was added to the church of Waters Upton St Michael that same year.

Picture credits. Atcham St Aeta: © Copyright Anji Carrier, taken from Geograph, modified, used, and made available for re-use under the terms of a Creative Commons licence. Waters Upton St Michael: © Copyright Richard Law, taken from Geograph, modified, used, and made available for re-use under the terms of a Creative Commons licence.

References

[1] John Venn, J. A. Venn (eds.) (1947), Alumni Cantabrigienses. Volume II. Part 3. Page 196. Copy previewed at Google Books.

[2] The Rev. Richard HALKE, M.A. At: Teresa’s Tree – Goatham Genealogy (website, accessed 1 Nov 2015).

[3] Monthly Magazine. No. 119, September 1804. Page 180. Copy viewed at Google Books.

[4] Weston-by-Welland, Northamptonshire, baptism register. Entry dated 28 Jun 1832 for John Thomas Halke. Copy viewed at Ancestry – Northamptonshire, England, Baptisms, 1813-1912. Indexed at FamilySearch, Batch I04386-4, Film 2000022, Ref ID item 4.

[5] Christ Church Cathedral, Canterbury, Kent, marriage register. Entry dated 23 Oct 1817 for The Revd. James Halke of Selling, Widower, and Mary Starr, Spinster. Copy viewed at Findmypast – Kent, Canterbury Archdeaconry Marriages 1538-1928. Indexed at FamilySearch, Batch I00751-7, Film 1786080, Ref ID it 2 p 8.

[6] Shrewsbury Chronicle, 7 Aug 1857, page 4.

[7] Shrewsbury Chronicle, 7 Oct 1859, page 6.

[8] Morning Post, 4 Jul 1859, page 3. Ecclesiastical Intelligence.

[9] Waters Upton, Shropshire, baptism register for 1815 to 1870. Copy viewed at Findmypast – Shropshire, parish registers browse, 1538-1900.

[10] Wellington Journal, 8 Oct 1859, page 3. District News. Atcham.

[11] Shrewsbury Chronicle, 7 Sep 1860, page 7. Waters Upton.

[12] Shrewsbury Chronicle, 4 Oct 1861, page 6. Uffington Harvest Festival.

[13] High Ercall, Shropshire, marriage register. Entry dated 14 May 1862 for Edward Ryley and Mary Ellen Atcherley.

[14] Staffordshire Advertiser, 18 Jun 1864, page 5. See Marriages at Waters Upton.

[15] Eddowes’s Shrewsbury Journal, 6 Apr 1864, page 6. Archidiaconal Visitation.

[16] Staffordshire Advertiser, 9 Jul 1864, page 4; 16 July 1864, page 4; 6 Aug 1864, page 4; 13 Aug 1864, page 4.

[17] Shrewsbury Chronicle, 12 Aug 1864, page 4.

[18] The Herts Guardian, 9 May 1865, page 4. A Church to be Rebuilt.

[19] Staffordshire Advertiser, 27 May 1865, page 3. Religious, Educational, &c.

[20] Staffordshire Advertiser, 5 Dec 1863, page 1. THE TRUSTEES of the late Mr. JOHN COBB respectfully announce that the Business of ARCHITECT, SURVEYOR, and BUILDER, carried on by him at Chetwynd-End, Newport, Shropshire, will be conducted heretofore, in all its branches, for the Benefit of his Family, by his Son, MR. J. F. COBB, For whom they earnestly solicit a continuance of the kind patronage so long and liberally extended to his late Father. Chetwynd-End, December 3rd, 1863.

[21] 1861 census of England and Wales. Piece 1901, Folio 79, Page 5. Chetwynd End, Chetwynd, Shropshire. Head: John Cobb, 48, architect & builder, born Newport. Wife Ann Cobb, 49, born Newport. Dau: Jane Cobb, 23, born Chetwynd. Dau: Mercy Cobb, 21, born Chetwynd. Son: John Cobb, 16, architect & builder’s clerk, born Chetwynd. Son: Willie [Walter] Cobb, 5, scholar, born Chetwynd. Plus 2 servants (housemaid, cook).

[22] George Edmund Street. At: Wikipedia (website, accessed 1 Nov 2015).

[23] List of new churches by G. E. Street. At: Wikipedia (website, accessed 1 Nov 2015).

[24] John Newman (2006), Shropshire. Page 672. Copy previewed at Google Books.

[25] Church of St Michael. At: Historic England website (accessed 1 Nov 2015).

[26] Eddowes’s Shrewsbury Journal, 16 Aug 1865, page 5. The Church.

[27] Shrewsbury Chronicle, 28 Dec 1866, page 7. Waters Upton.

[28] Withington, Shropshire, baptism register for 1813 to 1948. Copy (of portion from 1815 to 1900) viewed at Findmypast – Shropshire, parish registers browse, 1538-1900.

[29] Canterbury Journal, 8 Feb 1873, page 4.

[30] Kelly’s Directory of Shropshire, 1917.

[31] The Church. At: St. Michael’s Church Waters Upton (website, accessed 1 Nov 2015).