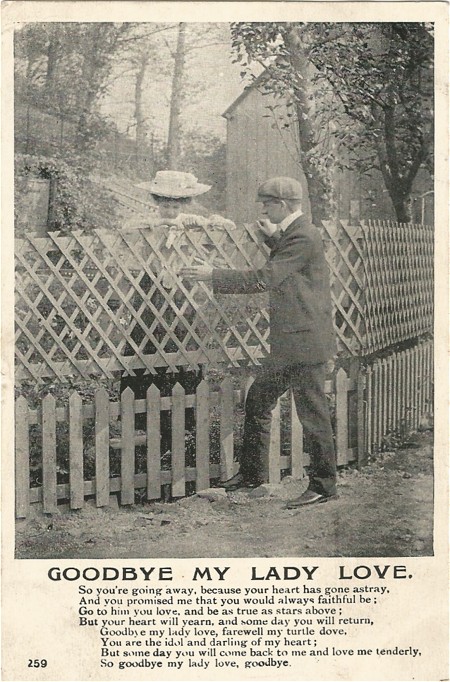

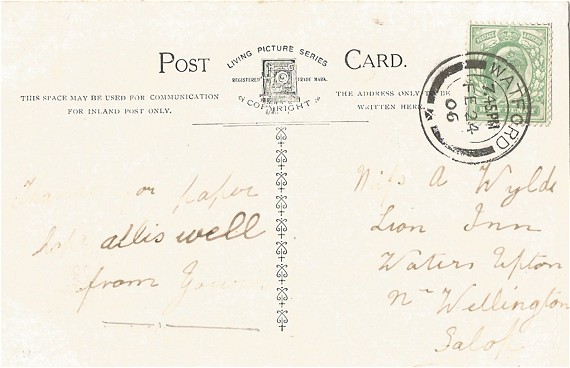

A little while ago I bought a postcard which bears a Waters Upton postmark. It does not add to my limited collection of village views – the scene on the rather grubby front of the card depicts Edgbaston Old Church, Birmingham. But it was probably posted by someone living in Waters Upton, or at least close enough for their mail to be franked there, someone named Elizabeth. Who was she?

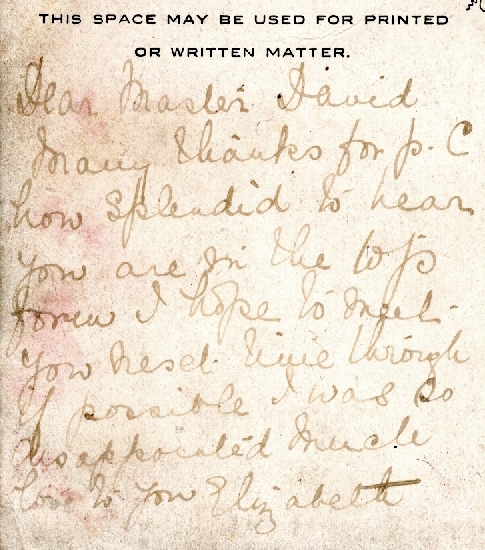

“Dear Master David” wrote Elizabeth, “Many thanks for P.C how splendid to hear you are in the top form I hope to meet you next time through [= though?] if possible I was so disappointed Much love to you”. The postcard was franked on 11 May 1908.

The recipient

At least the identity of the postcard’s recipient was fairly easy to establish. The card was addressed to Master D. G. Loveday, care of W. Deedes Esq, Mill Mead, Shrewsbury. At the top of the list of results when searching the 1901 census at Findmypast for D* G* Loveday is 4-year-old David G Loveday. He was living at the Manor House in Williamscote, in the Oxfordshire parish in which he was born: Cropredy.

The birth of David Goodwin Loveday, mother’s maiden name Cheape, was registered in the second quarter of 1896 in Banbury registration district ⇗. Googling David’s full name generates results from Wikipedia ⇗ and other websites, showing that he was born on 13 April 1896, was educated at Shrewsbury School, and was an Anglican bishop who died 7 April 1985.

I decided to find out more about David Loveday and his family in the hope that this might help to reveal the identity of Elizabeth. David’s father was John Edward Taylor Loveday. John was born in the first half of 1845 at East Ilsley in Berkshire, where his father (as per the censuses of 1851 ⇗ and 1861 ⇗) was Rector. He seems to be best known for printing, “with an Introduction and an Itinerary”, a manuscript by his great grandfather John Loveday ⇗: Diary of a Tour in 1732 through parts of England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. (This tour was probably number 23 in a list of 126 Tours by John Loveday ⇗ compiled by some of his descendants.) He was educated at Exeter College, Oxford ⇗, where he matriculated on 11 June 1862, aged 17.

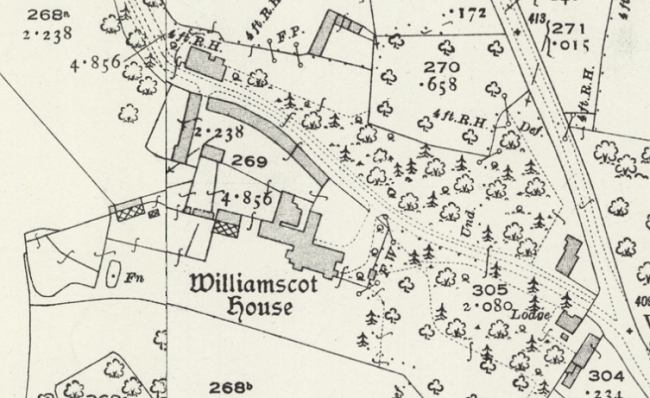

John Edward Taylor Loveday married ⇗ Edinburgh-born Margaret Cheape on 15 Oct 1874 at Cameron, in Fife, Scotland. The couple made their home at Williamscote House (the above-mentioned ‘Manor House’), where they were enumerated with their first five children in 1881 ⇗. John was described as a “Landed Proprietor & Magistrate for Counties of Oxford & Warwick”. They had five more children over the course of the next 15 years, of whom David Goodwin Loveday was the youngest.

It turns out that David was not the first of the Loveday children to spend time in Shrewsbury. The 1901 census ⇗ records his brother Henry Dodington Loveday, then aged 20 and an articled clerk to a solicitor, lodging with the family of clergyman William Leeke at the Abbey Foregate Vicarage. Another brother, Alexander, was also living in Shrewsbury when the 1901 census ⇗ was taken. Aged 12, he was boarding at the school his brother David would later attend, Mill Mead, a private establishment under the headmastership of Wyndham Deedes.

Elizabeth . . . who?

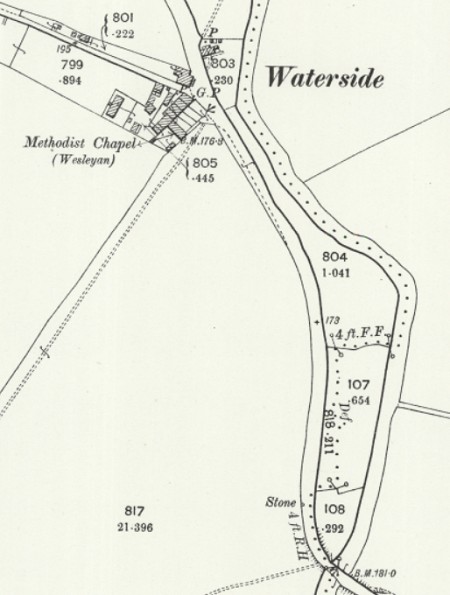

The Lovedays’ connections with Shrewsbury might explain how the mysterious Elizabeth became a friend of the family. Was there a lady of that name living in Waters Upton in the early 1900s who looks like a suitable candidate? Of the several Elizabeths on the 1901 and 1911 census returns for the parish, one stands out: Elizabeth Yonge.

Elizabeth Mary Hombersley Yonge, née Groucock, was the wife of the Rev Lyttleton Vernon Yonge. Rev Yonge was a son of Vernon George Yonge, also a clergyman, and part of a prominent Staffordshire family which had its seat at Charnes Hall. Lyttleton was born at the Rectory in Great Bolas, received his education at Cambridge, and although he resided at Waters Upton he was vicar of Rowton, in Ercall Magna parish. Elizabeth, who was also from the parish of Bolas Magna, was a daughter of Thomas Groucock (a farmer of 180 acres in 1881), and of Elizabeth Groucock née Dickin, who was descended on her mother’s side from the Wase family of Waters Upton Hall.

The social standing of the Yonges (and perhaps also the subject of the postcard’s picture) makes Elizabeth my top ‘suspect’ in a case which is not so much a ‘whodunnit’ as a ‘whopostedit’. All I am lacking is any direct evidence that the Yonges and the Lovedays actually knew each other!

Maybe one day I will find that David Goodwin Loveday’s early education, before he went to Shrewsbury School, was as a pupil boarding either with Lyttleton Vernon Yonge or with his fellow clergyman and Waters Upton resident, John Bayley Davies? Or perhaps I will find a document written (or least signed) by Elizabeth, so that I can compare it with the writing on the postcard at the centre of this mystery. Her signature should appear in the Waters Upton marriage register, but the register begun in 1837 is still in use and has not been deposited at Shropshire Archives. The probate copy of her will, a digitised version of which I have obtained from HMCTS via the Gov.UK website ⇗, is typewritten and bears no signature.

So is this the end of my investigation? Not quite. Because while looking at the other Elizabeths of Waters Upton, I found a further line of enquiry.

Coincidence or connection?

The Elizabeth who piqued my interest was Elizabeth Emma Ball. She was a daughter of William Abraham Richard Ball and his wife Sarah, née Cureton. This Elizabeth spent the early part of her adult life working as a servant before moving back to Waters Upton between 1901 and 1911. There is nothing to suggest that she met the Lovedays unless perhaps she worked for one or more of them as a servant, but if that was the case the development a postcard-exchanging relationship with David Goodwin Loveday seems unlikely. However, if she didn’t know the Lovedays personally, Elizabeth may have known of them, through her younger sister…

Mary Ann Ball was born at Waters Upton on 13 February 1877. By 1891, when she was 14, she was in service, working as a nurse for the family of John Bayley Davies at Waters Upton Rectory. A decade later she was in Shrewsbury, living and working as a housemaid at a house in Belle Vue Road. Then, in 1909, she married Thomas Henry Kimnell.

Thomas was born at Wardington in Oxfordshire on 25 August 1878 and was enumerated there with his family on the censuses of 1881 ⇗, 1891 ⇗, and 1901 ⇗. When the latter census was taken, Thomas was 22 and, like his father, he was an agricultural labourer. Whether his fortunes changed before or after his marriage is unclear, but change they most certainly did. The 1911 census ⇗ recorded him not as a labourer but as a farmer, working on his own account. With wife Mary Ann and daughter Eva Mary (born 14 March 1910) he was living at Williamscote in Wardington parish.

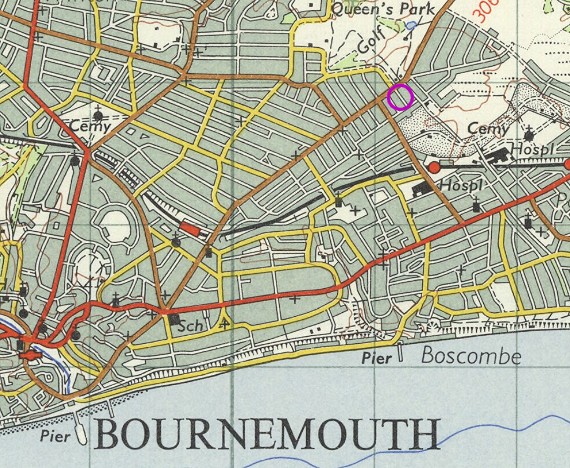

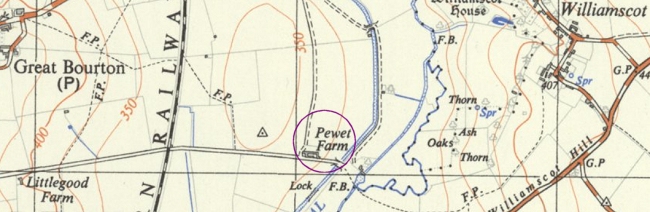

A second daughter, Helen Elizabeth, was born at Williamscote on 22 February 1914, but the Kimnells’ third and last child, Alice, was born at the end of 1917 or in the first quarter of 1918 on the other side of the River Cherwell in the parish of Bourton. Almost certainly the family was living there when the Banbury Guardian of 5 Jul 1917 reported on a military tribunal at which Thomas, a farmer of 107 acres, successful claimed exemption. From the 1921 census and National Identity Register of 1939 it appears that the family remained there for more than 20 years, at Pewet / Peewit Farm (highlighted on the map above).

Thomas Henry Kimnell of Williamscote died on 16 June 1965 at Woodford Halse in Northamptonshire; his estate was valued at £4531. Mary was also of Williamscote at the time of her death on 17 February 1969; given that her death was registered at Daventry she too may have died at Woodford.

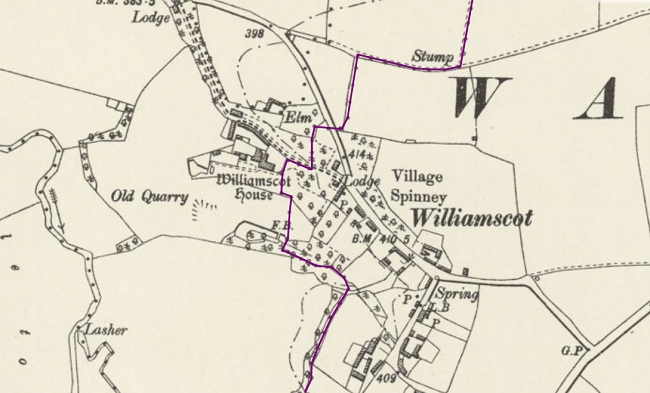

Did the references to Williamscote in the preceding paragraphs cause you to think back to the earlier part of this story, relating to the Loveday family? The hamlet of Williamscote, although lying in the parish of Wardington, is a stones-throw from Williamscote House in neighbouring Cropredy parish (the boundary is shown in purple on the map below). The 1911 Kelly’s Directory ⇗ of Oxfordshire lists Thomas H Kimnell right after John Edward Taylor Loveday under Williamscote! Coincidence? Quite possibly, but I think there’s a good chance that it isn’t.

William Ball was well known in Waters Upton so both the Davies family and the Yonges would have been familiar with his daughters, all the more so in the case of Mary Ann given her employment at the Rectory. If, as I have theorised, Elizabeth Yonge was a friend of the Lovedays, this might mean that she was in a position to help bring about the union of Thomas Henry Kimnell (who the Lovedays may have known, perhaps as an employee?) and Mary Ann Ball.

Ultimately, this is speculation and does not prove anything conclusively. The puzzle of the postcard’s sender remains officially unsolved – a one-place study ‘X File’. At least for now. One further possibility for acquiring a sample of Elizabeth Yonge’s handwriting and/or signature remains. Dave Annal recently reported on Twitter that he managed to obtain a copy of an original will from HMCTS – although he did have to wait 16 months!

Picture credits: Front and back of postcard, author’s own images. Extract from Ordnance Survey 25 Inch mapping (1892-1914) showing Williamscot House ⇗ reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland ⇗ under a Creative Commons licence ⇗. Extract from Ordnance Survey 1:25,000 mapping (1937-61) showing Great Bourton, Pewet Farm and Williamscot ⇗ reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland ⇗ under a Creative Commons licence ⇗. Extract from Ordnance Survey 6 Inch mapping (1888-1913) showing Williamscot House and Williamscot ⇗ reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland ⇗ under a Creative Commons licence ⇗.