⇐ Back to Part 1

So far (in part 1 of this article) I have looked at rivers, bridges and inns as landmarks which would have been familiar and significant to people living in, visiting, or passing through Waters Upton. There were of course other buildings besides the pubs which could be considered landmarks, contributing to the unique character and identity of the village, including the church of St Michael’s and the Hall, set in its centre. I have written about the construction of modern-day St Michael’s in John Thomas Halke and the Church of Waters Upton; the church will feature again in future stories here, along with other buildings in Waters Upton. The landmark I am going to focus on now however, is one which lies several miles away from the parish.

View to a Hill

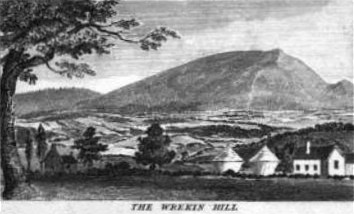

Head south out of Waters Upton on the A422 and almost immediately you will see a hill in the far distance. (Note: If you’re driving when you do this, keep a close eye on the road as well!) It doesn’t look like much from this distance, and to be fair, it’s not even in the top twenty of the highest Shropshire hills ⇗. Size isn’t everything however, and this landmark’s stature belies its significance within and even beyond the county. Say hello to the Wrekin.

The Wrekin has been described as “our best known hill and an iconic landmark for miles around” (see link above). On learning that the hill is only 407 meters (1,335 feet) above sea level, you might wonder why it is regarded with such affection. Roly Smith, writing in The Guardian ⇗ in 2000, explains: “the Wrekin, which always proudly and significantly carries the definite article, is undoubtedly a hill with a presence. It rises so sharply and unexpectedly from the pastoral Severn Plain that it forces you to notice it.” He then added, “There are few mountains in Britain, let alone hills, that have exerted the same powerful influence or sense of place on its surrounding communities.”

The Wrekin stands out. It is not a mountain, but a drop of over 150 metres on all sides ⇗ gives the Wrekin a certain prominence, especially in a landscape which is otherwise relatively flat – and also qualifies it as a ‘Marilyn’ ⇗. The Wrekin’s nearest Marilyn neighbours, Caer Caradoc and Brown Clee, are respectively about 20 and 30 kilometres away in Shropshire’s much hillier south.

This prominence means that the Wrekin can be seen for many miles around, particularly from the north and east. As people travel into Shropshire from that latter compass point, on the M54 for example, the Wrekin stands a welcoming beacon. It calls for people to climb to its summit, and those who do are rewarded with outstanding views ⇗.

Dead Poets Society

The Rev Richard Corfield, Rector of Waters Upton from 1822 to 1865 (he was also Rector of Pitchford, where he spent much of his time), was one of many Shropshire souls familiar with the sights to be seen from the top of the Wrekin. He was also one of several authors who have set out their appreciation of the Wrekin in verse, albeit with a little poetic licence. The poem (dated 14 February 1833) can be read in full in Shropshire Notes and Queries ⇗; the following is an abridged version:

From Wrekin’s summit cast the eye around,

To view the objects which th’ Horizon bound;

O’er Salop’s plains with beauteous verdure drest,

The Cambrian Mountains stretch along the West.

The darksome Berwyn scowls with aspect drear,

Till Dinas Bran, and Moel Pam’ appear.

Turn to the North, and Hawkstone hills you see,

With Cheshire prospects reaching to the Dee.

When to the East, you bend th’ admiring gaze,

The barren Peak your startl’d thoughts amaze!

More Eastward still, you ken in distant view

Edge-Hill, where Charles his faithful follow’rs drew.

But dwell not here on scenes of discord past,

Look tow’rds the South, the prospect brightens fast;

The far fam’d Malvern breaks upon the eye,

And balmy breezes waft from Southern sky.

This fairy circle let us onward trace,

O’er Brecons beacons, Radnor’s forest chase;

And whilst on Caerdoc’s sister hills we stop,

In distant outline, lo! Plinlimmon’s top.

May then this mountain, fair Salopia’s pride,

Attract our footsteps to its summits side;

The summit gain’d, the weary toil’s repaid,

By prospects varied, mountain, wood, and glade;

And as the outline may be further known,

So past its limits may our love be shewn—

Love to our County—and to all held dear

By ties of kindred, friendship’s off’ring bear—

Love to our Country—and, to all friends round

The Wrekin’s circle, may our love resound—

Such wishes these all Shropshire hearts inspire,

In social converse round the Winter’s fire.

School of Rock

Waters Uptonians were as familiar with the Wrekin as any Salopians. We have already seen the hill can be seen from the road just south of the village, and in John Morgan, surgeon and apothecary of Waters Upton – Part 1 I included a notice advertising the availability of a “genteel residence” within the village which had “a commanding view of the Wrekin and surrounding country.” Such was the lure of this landmark that many made the journey to become more personally acquainted with it, including the children of the parish, for whom excursions to the Wrekin were arranged as an annual treat in the latter part of the 1800s.

The earliest reference to such visits that I have found so far actually relates to the children of the ‘Union School’ just beyond the Waters Upton parish boundary; a report published in the Shrewsbury Chronicle on 7 September 1860 noted: “At the last guardians meeting it was unanimously resolved on the motion of Mr. Minor, vice chairman, to give the children of the Industrial School, at Waters Upton, holiday to visit the Wrekin.” Almost thirty years on from that, a delightfully detailed description of a trip laid on for the village’s own children appeared in the Wellington Journal of 17 August 1889:

You will be pleased to know that better conditions blessed at least one subsequent school outing to the Wrekin. In July 1896, when 78 children and 40 accompanying friends headed for the hill in waggons “lent by Mr. H. F. Percival, Mr. S. Dickin, and Mr. W. Jerman”, they were “favoured with fine weather” and S (Samuel) Tudor once again provided tea. Several of those named in these reports will be familiar if you have read Late Victorian Christmases in Waters Upton; the others I will have to introduce you to in future articles.

This is the end

In my conclusion to part 1 of this article, I mentioned “the usual loyal and patriotic toasts” which were honoured in Waters Upton’s Swan Inn, in 1896. These would almost certainly have included one which the Rev Richard Corfield slipped in to his poem of 1833, namely “To all friends round the Wrekin”. (This should not to be confused with the saying “all around the Wrekin”, which has a similar meaning to “all round the houses” – or in other words, taking a longer route than necessary!)

The oldest appearance I have found in print of “all friends round the Wrekin” dates back to around 1706, when playwright George Farquhar used it to open the published version of his Shropshire-based comedy The Recruiting Officer ⇗ (the image above is from Google’s electronic version of this long out of copyright work). Clearly it was well-established even then. I have found many later references to this toast in Shropshire newspapers – it appears that the tradition was to make it the final toast after all the others had been offered and drunk to, by way of recognising the special bond between those connected by their county’s most revered landmark. Although I have not yet found any specific references to its use in Waters Upton, I have no doubt that it was spoken there, often, and with feeling.

Picture credits. View of the Wrekin from Waters Upton: Embedded from Google Maps. The Wrekin hill: From the electronic version of The History and Antiquities of Shrewsbury, volume II (published about 1837 and therefore out of copyright) at Google Books ⇗. View from the Wrekin: Photo by Wikimedia Commons ⇗ contributor Northerner, modified and used under a Creative Commons licence ⇗. View of the Wrekin: From a postcard postmarked 1906 (in my own collection), out of copyright. To all friends round the Wrekin: From the electronic version of The Recruiting Officer (published about 1706 and therefore out of copyright) at Google Books (link in text above).