For my first contribution towards a Waters Upton house history I’m going to look at one of the few older properties in the parish which can, throughout its existence, be identified by name in most records relating to it. Today it is the Bharat Indian Restaurant ⇗, and for a while in the 1800s it was known as the New Inn, but for most of its near 200 year history this home and business premises was named the Lion Inn.

Before I attempt to give the Lion the House Through Time ⇗ treatment, I should explain what I mean by ‘towards a house history’. Because of data protection and privacy requirements, and the related issue of more recent records being less accessible, my one-place study of Waters Upton officially ends around the beginning of the Second World War. The same will apply to the accounts of the houses of the parish which I am compiling and will share on this website. In the case of properties which still stand, I will of course include information about them as they are today, but there will be about eight decades of their most recent histories missing. That still leaves a decent period of time for us to look at!

In addition, this post (and others like it, to follow in due course) will provide only an introduction to the people connected with the house. The owners and/or occupants who I have managed to identify will be discussed briefly, with the aim of exploring their stories in more detail later. When those stories are added, I will update this post to include links to them.

Finally, I have yet to consult all of the available records. There are electoral registers and more besides held at Shropshire Archives in Shrewsbury, patiently waiting for me to take a look at them and extract the data they hold. Rather than wait until I have done so before embarking on this house history journey however, I have chosen to share what I have, knowing that I can update things later. I’ll now get on with doing exactly that.

Inn like a Lion…

A notice published on the front page of the Shrewsbury Chronicle of 21 June 1833 provides a beginning for the Lion’s story, nearly two centuries ago:

FREEHOLD PROPERTY,

At Waters Upton and Wellington.

TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION,

By Mr. WYLEY,

What a wonderfully informative notice! Not only do we find from this that the Lion was “newly-erected”, we also get an impression of the house itself, with its “excellent Cellaring” and those “spacious and commodious” rooms.

The 1911 census recorded that the building had seven rooms (including the kitchen but not including any scullery, landing, lobby, bathroom or closets); the 1921 census says nine. The reason for the apparent increase is not clear. The building might have been extended between the censuses, or a couple of rooms may have been divided. Or the head of the household – the same person in both years – may simply have interpreted the instructions differently on each occasion. Curiously, the room count for the nearby Swan Inn went from nine in 1911 to seven in 1921!

Pride of place

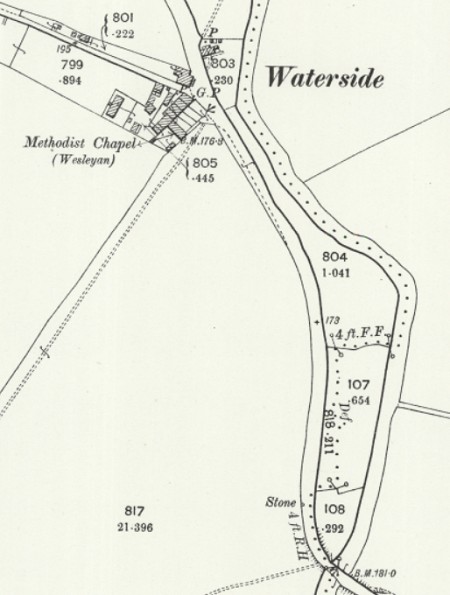

Amongst the other information in the 1833 auction notice is a description of the Lion’s location. The house stands on the East side of what is now the A442, the Wellington to Hodnet and Whitchurch road, on the South side of its junction with the main road through Waters Upton village (from which a far from direct route to Market Drayton can be followed). An ideal location to tempt thirsty travellers or workers (such as waggoners) passing by, while also being well situated for local customers.

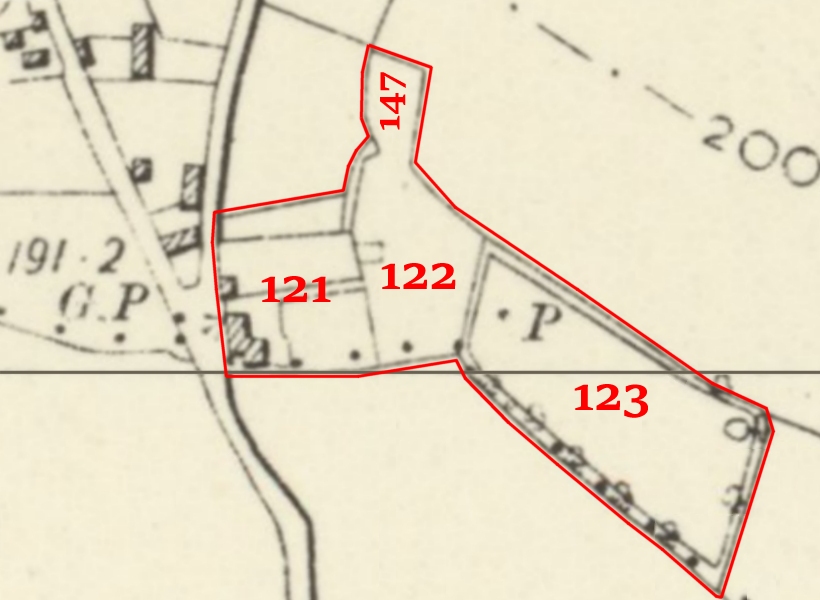

The other buildings belonging to the Lion – “Stables, Cowhouses, […] and Premises” – and adjoining parcels of land occupied along with the house (and its walled garden) – “Four small Pieces of good Meadow and Pasture […] containing three Acres or thereabouts” – are also noted in the auction notice.

The tithe map and apportionment records created in 1837 provide details of at least some of these pieces of land. A “House [Buildings] Garden & Croft” (number 121 on the tithe map) corresponds with the Lion’s location. The owner of that property also possessed Middle Marsh (122, pasture, two roods and 20 perches in extent), Lower Marsh (123, meadow, one acres, two roods and 28 perches) and piece of land described as a Garden (147, no description of cultivation given, 25 perches in extent). Below, on an extract from a later (Ordnance Survey) map, I have drawn a line to indicate the boundary of those pieces of land and added the numbers from the tithe map.

The nature of the beast

Another snippet from the notice of the Lion’s sale in 1833: the property was described as a “PUBLIC HOUSE, or Licenced Beer House”. It seems likely that the Lion was one of the thousands of new public houses which appeared in the wake of the Beerhouse Act 1830 ⇗. Under this Act any rate payer could apply for a licence (costing two guinea annually) to brew and sell beer on their premises.

No clue as to the original owner of the Lion and its associated land is given in the notice of sale, but the above-mentioned tithe apportionment records of 1837 probably tell us who purchased the property – although there is some confusion over his exact identity. The apportionment agreement referred to a William Felton as “the Owner of a Messuage Garden and several Closes of Land containing by Estimation Three Acres and twenty two perches Statute Measure”. However the accompanying schedule names the landowner as Thomas Felton – perhaps the same Thomas Felton who appeared on the 1841 census at Waters Upton as a publican.

I have my doubts about Thomas being the owner, not least because the register of voters for 1842-43 includes William Felton, with abodes at Rowton and Waters Upton, as the owner of a “Freehold house and land” at Waters Upton – occupied by Thomas Felton. Subsequent registers, up to that of 1850-51, state that William Felton had his abode at Bratton in the parish of Wrockwardine, and referred to his house and land at Waters Upton as the Lion Inn.

William Felton does not appear as a Waters Upton voter in the electoral registers after 1850-51. This corresponds with the death ⇗ of a 77-year-old William Felton, registered in Wellington Registration District in the first quarter of 1851. I believe he was the William Felton enumerated on the 1841 census ⇗ at Rowton as a farmer, his age (likely rounded down) given as 65. It appears that his son John Felton then inherited the Lion – and went on to change its name.

Between the Lions

John Felton of Bratton appeared in the lists of voters as the owner of a freehold house and land at Waters Upton before his father’s death. He was likely the John Felton, son of William and Sarah, baptised ⇗ 25 May 1806 at Kinnersley (nowadays Kynnersley). He wed Melona Meredith ⇗ at High Ercall on 2 October 1837, at which time (according to the allegation made when he applied for his marriage licence ⇗) he was a butcher. In 1851 he was recorded on the census ⇗ as a farmer of 184 acres, living with wife Melona and their children at Long Lane in the parish of Wrockwardine.

John’s property in Waters Upton was not identified by the name of the house or its occupier in the aforementioned lists. Similar entries in those lists continued up to and including that of 1858-59. Then, from 1859-60 until at least 1871, we see John Felton of “Long Lane, near Wellington, Salop” as the owner of a freehold house and land at Waters Upton named as the New Inn.

The establishment formerly known as the Lion appears as the New Inn on the censuses of 1861 and 1871. During the 1870s however the inn’s original name was restored – the earliest reference I have found so far is in a report in the Wellington Journal of 14 October 1876 (page 8). The Lion’s return may well have been a consequence of the death – on 19 July 1875 at Long Lane according his entry in that year’s probate calendar – of John Felton.

I have yet to trace the ownership of the Lion from 1875, although I do know (thanks to the Shrewsbury Chronicle of 1 March 1907, page 8) that on 28 February 1907 “the ‘Lion’ public house, at Waters Upton, with some 3 acres of land, was sold to Mr. W. T. Southam, Shrewsbury, for £850.” There are however other people connected with the history of this house for us to look at – particularly those who lived there and called it home. I will introduce them to you in Part 2.

To be continued.

The Lion Inn, between its days as an inn and its current existence as the Bharat Indian Restaurant. Photo by Harry Pope, taken from Flickr ⇗ and used under a Creative Commons licence ⇗.