So began a particularly sad story which appeared in the Shrewsbury Chronicle on 29 June 1883. A slightly sensationalised story too, I think, for not only was the deceased not murdered, his body had not been mutilated. What were the circumstances of the body’s discovery? Who was the unfortunate man? And, since I’m telling his story here, how was he connected to Waters Upton? Let’s return to the Chronicle’s report (to which I have made one small correction).

Poor William! How did he end up living, and dying, in such wretched circumstances?

A native of Waters Upton

Piecing together the story of William Lloyd’s origins and early years is not straightforward, so bear with me while I assemble all the evidence – or skip to the next section if you wish! If, as Joseph Rogers stated, William was about 50 at the time of his death, he would have been born around 1833. I believe that Joseph’s estimate of William’s age was a ‘rounding up’ and that William was the 5-year-old William Lloyd who was enumerated on the 1841 census, at Waters Upton, with John and Ann Williams (ages rounded down to 50 and 40 respectively), Joseph Lloyd (12), and Elizabeth Lloyd (7).

Unfortunately the 1841 census did not record the relationships between household members so this record provides fairly limited information about William and those he shared a home with. There’s no baptism record for him that I can find either, nor does there appear to be one for Elizabeth Lloyd. Joseph Lloyd however was baptised at Waters Upton on 22 June 1828, his parents were William Lloyd (a labourer) and Ann, whose abode was in the parish. Were these two also the parents of Elizabeth and of the younger William Lloyd?

The most likely marriage for Joseph’s parents was that which took place at Wellington on 3 February 1827 ⇗. The parish register described the couple as “William Lloyd of this Parish and Anne Taylor of this Parish”. William died in 1835, at the age of 37, and was buried at Waters Upton on 23 Sep that year. (His age at death (37) likely makes him the the son of William and Elizabeth Lloyd who was baptised at Waters Upton on 19 Jun 1798.) Ann then remarried in 1840, to widower William Taylor, their entry in the register naming Ann’s father as James Taylor.

The 1851 census shows John and Ann Williams as husband and wife, but with none of the Lloyd children from 1841 living under their roof. John, aged 63 and an agricultural labourer (as he had been in 1841), was born in Waters Upton; the relevant baptism is likely that of John, son of William and Mary Williams, “in ye Sch: Room” on 1 June 1789. Ann, 51, was born in Cherrington; almost certainly she was “Anne Daur of James & Anne Taylor, Cherrington” baptised at Tibberton ⇗ on 21 April 1799.

William Lloyd too was living in Waters Upton in 1851. Aged 15, he was a hostler residing with and working for publican William Matthews. The pub is not named on the census schedule but there is little doubt that it was the Lion, as the Swan Inn – the only other hostelry in the village – was identified by the enumerator elsewhere.

The census of 1861 adds to the evidence relating to William Lloyd’s family, as well as providing an update on his fortunes. Household schedule 42 recorded agricultural labourer John Williams, 72, with his wife Ann, 61, and two sons (actually, stepsons), Joseph and William Lloyd. Joseph, aged 32 and unmarried, was by this time working as a gardener. William, 25, also unmarried, was an ‘ag lab’ like his stepfather.

Elizabeth Lloyd had married by this time, and the record of that event ⇗ – naming her father as William Lloyd – adds further evidence to back the theory that she, Joseph, and William Lloyd junior were siblings. She wed James Tomkinson on 6 November 1854, probably at Chetwynd where she had been enumerated as a servant on the 1851 census ⇗ (name transcribed as Mary Hary by FamilySearch!!). She and James spent the rest of their days in nearby Newport, where they had 11 children.

John Williams of Waters Upton died on 26 November 1864, aged 75. The death of Ann Williams, formerly Lloyd, née Taylor, was registered in Wellington Registration District, in the last quarter of 1886; she was 87 but her age was recorded as 86. Joseph Lloyd’s story, which involved duck stealing, I will continue another time. That leaves William Lloyd, whose story I will now conclude.

A vagrant life

William Lloyd’s next appearance on a census, in 1871, seems to have been his last. He had left Waters Upton by this time, and was once more working, this time as a labourer, for an inn keeper: James Brown of the Green Dragon at Hadley. At some point over the next ten years however, something happened which changed William’s way of life – he became homeless. I have not found him on the 1881 census, but I can’t rule out the possibility that was enumerated as a nameless tramp found sheltering under a hedge or in a barn or outbuilding.

The report from the Shrewsbury Chronicle, part of which I quoted at the beginning of this story, was one of several arising from the inquest into William Lloyd’s death; others appeared in the Shrewsbury Journal, 27 June 1883, and the Wellington Journal, 30 June 1883. Together, they provide snippets of information which taken together give us a feel for how William spent his last years, and in particular his final months. It was said that William “had led a vagrant life for some years, sleeping in outbuildings and picking up a living as best he could.” Joseph Rogers, who “had known the deceased from a lad”, also stated that for a long time William “had been going about the country labouring with thrashing machines, and was formerly in the employ of Mr Price, of The Lees, near Walcot.” He was not married, and “had been in the habit of sleeping out.” I can only guess that at some point in the 1870s a spell of unemployment left William without the means to pay for accommodation and led to him taking advantage of whatever shelter and odd jobs he could find, whenever and wherever he was able to. Returning to the Shrewsbury Chronicle:

Another witness was John Thomas, described by one paper as a waggoner and by another as a cowman. He worked for Mr Bromley, at whose house the inquest was heldOn Sunday, the 27 May 1883, Mr Thomas saw William Lloyd lying down “on the top of an old stack bottom” with “some hay partially thrown over him.”

The two men had a conversation, in which William said that he had gone to the place where John found him “on the Saturday night, that he lay in the shed, and that he had come out to sun himself. He said he had been very poorly for some time, suffering from bronchitis”, and as a result of that illness “he had a bad cough”. William also said that “he had been following machines belonging to Mr. Nicholls and Mr. Powell, of Shrewsbury” and that “most of his food had consisted of water.”

A most melancholy case

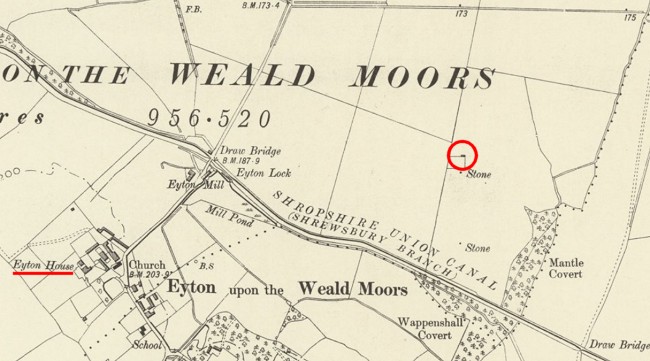

John Thomas was probably the last person to see William Lloyd alive – and the last person to see him at all for several weeks. There was no public road where William had settled, although the canal and a path leading to Kynnersley were not far away. With the hay in which William slept not being needed at that time, no one went near the stack until Sunday 24 June 1883.

William Lloyd’s body was found that day by two boys. One of them, Walter Ruscoe, lived at Sidney (or Sydney) in the parish of Kynnersley (or Kinnersley) and was, like John Thomas, employed by Mr Bromley. On the day in question he took a bull down to the weald moors, and on his return he found the body by the haystack, half covered with hay. He quickly gave the alarm which led to the police becoming involved, and an inquest taking place the next day.

At that inquest the jury gave a verdict of “Found dead” or, according to the Wellington Journal, “Death from natural causes.” The Coroner said “that it was a most melancholy case; but there was no ground whatever to suppose that deceased had met with any violence. He had apparently laid down and been overcome. It was a matter of regret that deceased had not taken the advice of one of the witnesses, and gone to the Workhouse.”

Article updated Feb 2026.

Picture credits. Map: Extract from Ordnance Survey Six Inch map Sheet XXXVI.NW ⇗ published 1902; reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland and used under a Creative Commons licence ⇗. Family tree diagram: By the author. Drain on Eyton Moor: Photo © Copyright Richard Law; taken from Geograph ⇗ and modified, used and made available for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence ⇗. Eyton House: Photo © Copyright Chris Downer; taken from Geograph ⇗ and modified, used and made available for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence ⇗.