⇐ Part 1

Edgar Percy Davies now retraced his steps back along the village road, heading towards and then beyond the church. Soon he was passing the White House, his destination being the next house along.

Number 11 was occupied by newcomers to the village, the Rowberry family. Thomas Henry Rowberry may well have served during the war – there are two sets of medal award records (one from the Machine Gun Corps and one from King’s Royal Rifle Corps), either of which might be his, but no pension index/ledger cards or surviving service record to confirm this.

Beyond number 11 lay the semi-detached residences numbers 10 and 9, headed respectively by (post-war incomers?) Joseph Ralphs and his son Frank Ralphs. I am not aware of any wartime military service being undertaken by members of this family, but it would not surprise me if Frank or one (or more) of his brothers had served.

Why did the enumerator cross the road? To collect the household schedules on the other side. Number 31 (Clematis Cottage) was the home of Arthur Ball and his sister Elizabeth Emma, neither of whom had connections with military service that I know of. The same cannot be said of the next house however.

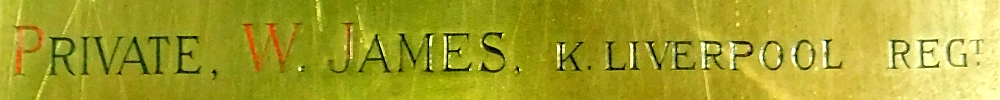

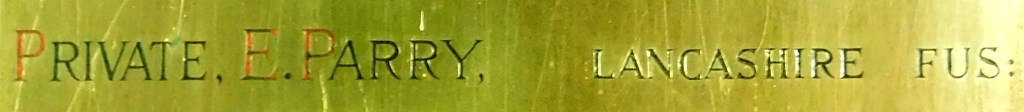

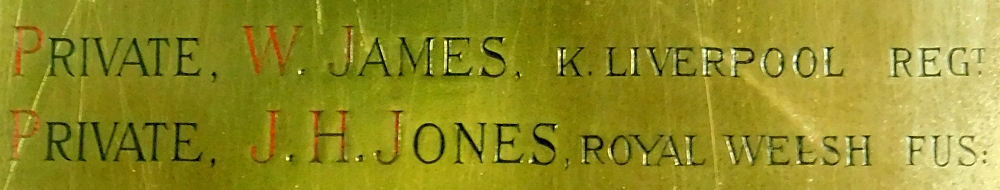

At number 32 lived widower Charles George, along with two of his daughters, both war widows, and their children. Jane’s husband William James, a native of Waters Upton, I have already mentioned (his mother lived at number 23 Waters Upton). Kate’s husband John Herbert Jones was a Liverpudlian, who was killed in action while fighting with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in France. A few years after this census was taken Jane and Kate would both emigrate, with their children, to start new lives New Zealand.

On went enumerator Davies to numbers 33 (William and Matthews) and 34 (William Edward Morgan and family), and then, after crossing road, to number 8. The occupant of this house, Alfred Ridgway, I have already mentioned (his first cousin Charles, the blacksmith, lived at number 15). Alfred, a carpenter and wheelwright, had two sons who, despite having no medals to show for it, had ‘done their bit’ during the war: William George Ridgway (Devonshire Regiment and Labour Corps) and Alfred John Ridgway (Royal Garrison Artillery).

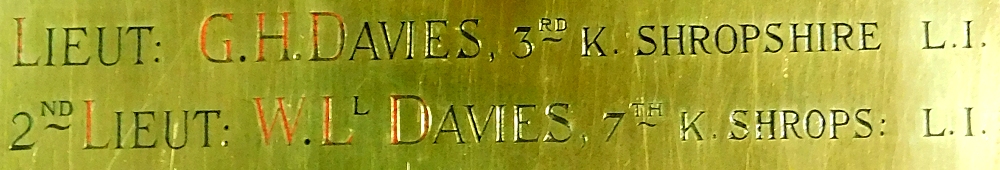

Back across the road to Malt House Farm and, just to the North of that, Lower House Farm, both occupied by (unrelated, as far as I know) Powell families. These farming families had no wartime military connections that I know of, but one of the servants at Lower House Farm did: Thomas Hall (who would marry his employer’s sister in 1922) served with the Royal Army Veterinary Corps. His brother, Pryce Hall, also played his part in the Great War. Having emigrated to Australia in 1912, Pryce served with the Australian Imperial Force from 1915.

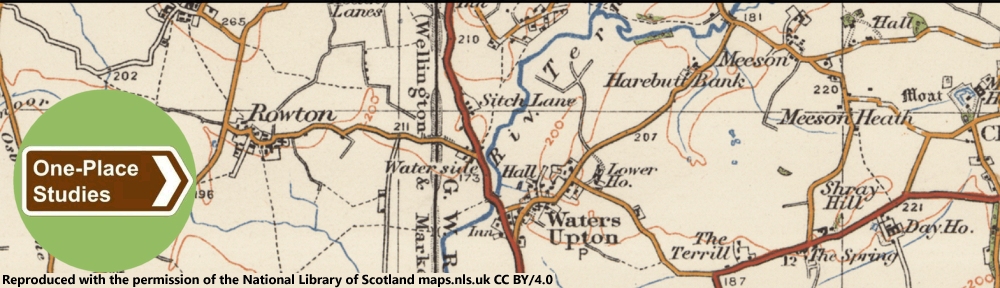

On leaving Lower House Edgar Davies continued along the road, which now left the village of Waters Upton, and headed towards Harebutt Bank. He called next on number 39, which was occupied by the Cartwright family. John, the head of the household, had no military record but his younger brother James did. James Cartwright enlisted with the Monmouth Regiment, then transferred to the South Wales Borderers after entering France with the British Expeditionary Force. He was discharged after receiving a gunshot wound to the left thigh in 1917, and died in 1919.

Edgar had already visited one home where relatives of John Evans lived (number 25), and now he called on another, number 40, where John’s uncle and aunt Samuel and Martha Evans lived. After that, he went to Harebutts Farm (number 38), home of the Casewell family. The Casewells’ servant, agricultural worker Alan Furnivall, had joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 and transferred to the RAF on its formation in 1918. Alan worked on aircraft rather than flying them, and he was discharged in 1920 with a record featuring a long list of civil convictions and prison sentences.

As he began to head back towards the Waters Upton village, Edgar the enumerator collected a final schedule from a Harebutt Bank household (The Harebutts, number 37, home of John Stanley Morgan and family). Then he continued along the road, past Lower House Farm, and turned left onto Catsbritch Lane.

On the right as he entered the lane was a dwelling divided into three, numbers 7, 6 and 5. These households were occupied by Elizabeth Matthews (at number 7), Frank and Annie Battman (at number 6), and William Beech with his wife Elizabeth and son Thomas (at number 5). Thomas Beech had been a Private with the Shropshire Yeomanry and then a Driver with Royal Field Artillery during the Great War, while his brother Henry Eddowes Beech (now living elsewhere) had emulated the latter part of his service.

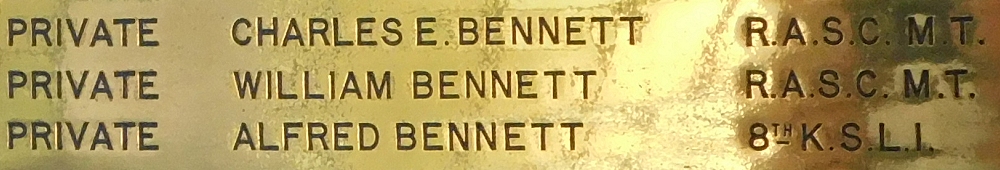

Just a little further along Catsbritch Lane and on the same side of the road was a terrace of four houses where Waters Upton’s street numbers began: number 4 (Charles James and family), number 3 (Ernest Edward Austin and family), number 2 (Joshua Cartwright and family), and number 1 (Thomas Bennett and family). All but one of these (number 3) houses had connections with military service in the Great War. Of those three, two have already been mentioned: Charles James at number 4 (a brother of Thomas James at number 23, of John James and the late Williams James, and a brother-in-law of William’s widow Jane James at number 32), and Thomas Bennett at number 1 (a brother of Alfred, George and Charles Edward Bennett at number 17).

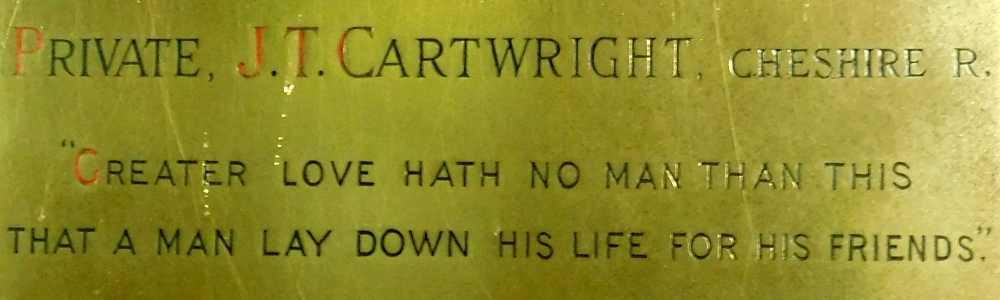

That leaves number 2 Waters Upton, the last household Edgar Davies would visit in which a family member had been lost during the war: Joshua and Priscilla Cartwright’s son John Thomas Cartwright was killed in action while fighting with the Cheshire Regiment during the Second Battle of the Somme on 27 March 1918.

A little further along Catsbritch Lane, and set back from it on the other side, was The Grange Farm (number 41?). The head of this household was Ferdinand Heyne, a naturalised British Subject born in Germany. Ferdinand was a pork butcher in Shrewsbury from at least 1901 until 1913 (when he listed in that year’s Kelly’s Directory) and possibly a little later, but not in 1917. Had anti-German sentiment during the war pushed him out of the town and into the countryside?

The next house at which Edgar Davies stopped to collect a census schedule was number 48. I must admit that I’m not entirely clear about the numbering along Catsbritch Lane, but I suspect that number 48 was the cottage now known as Manor Lodge, which sits beside one of the entrances to Waters Upton Manor (which might be number 49). It was occupied by James Evans, his wife, and their children, one of whom was John Evans. John had enlisted with the RAF in July 1918, just 11 days after his 18th birthday and a little over three months before the war ended.

At the Manor itself – not that it was named (or numbered) on the schedule – was Arthur Lea Juckes. Arthur had a little military service to his name, in the form of a brief spell as a Lieutenant with the Surma Valley Light Horse in India, but that was in 1898. During the Great War he took on another role, chairing military tribunals at Wellington – and ruthlessly enforcing the rules under which men could be conscripted.

As he got closer to The Terrill, the end of our enumerator’s tour of Waters Upton was nearly over. He visited number 42 (farmer Richard Allen and his housekeeper – was this Melverley House or Linden Lea?) and then number 44 (Thomas Edward Harris and family; I’m guessing that number 43 – Grange Cottage? – was unoccupied).

Edgar Davies’ penultimate house call was to number 45, The Terrill Farm, occupied by septuagenarian farmer William Woolley, his wife Emma, two of their daughters, and three visiting relatives. Four of William’s sons had participated in the Great War: George Woolley (Yorkshire Regiment and Labour Corps), Robert Woolley (Canadian Royal Engineers), Frederick Woolley (Royal Engineers), and William Woolley (Royal Field Artillery).

Finally came number 46, a cottage just North of the Terrill Farm (number 47, a little further to the North, was most likely unoccupied). This was the home of widow Sarah Cartwright and two of her grandsons, one of whom was Geoffrey Henry Cartwright. It appears that Geoffrey first enlisted with the Black Watch (possibly before the war), then fought with the Worcester Regiment (when he was wounded at Gallipoli), and went on to serve with the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Regiment and finally, post-war, with the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (Territorial Army). He was the third resident of Waters Upton parish to declare himself as being out of work – all three were former servicemen.

Life went on in Waters Upton after the First World War, as it did elsewhere, but without those who paid the ultimate price to help deliver victory over the Central Powers, and with many who came home bearing physical injuries, mental scars, memories of battle which would never fade. Directly and indirectly, the lives of many of Waters Upton’s inhabitants were forever changed. More than a century later, we remember those who died, those who returned, and the families and communities they belonged to.