⇐ Back to Part 2

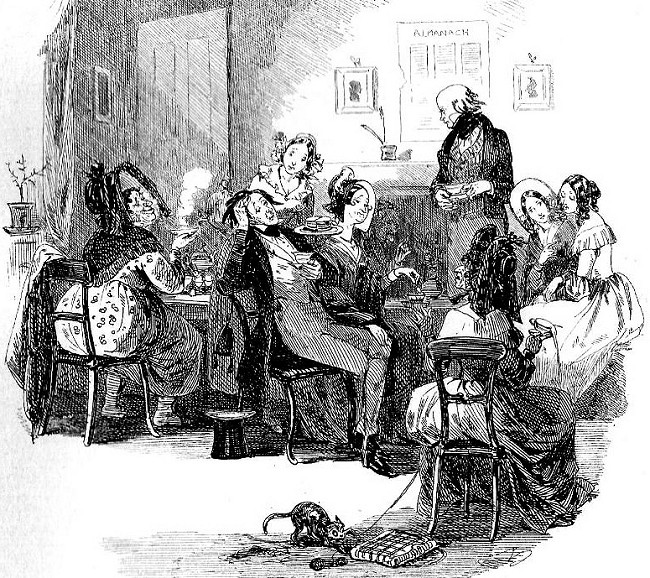

What an interesting evening this is turning out to be – I must travel back to the Waters Upton area in the late 1860s more often! ‘Local talent’ performing along with accomplished amateur vocalists and musicians from a little further afield is proving to be a great combination. Speaking of those who have come from beyond the immediate locality, here comes Mr Palmer again.

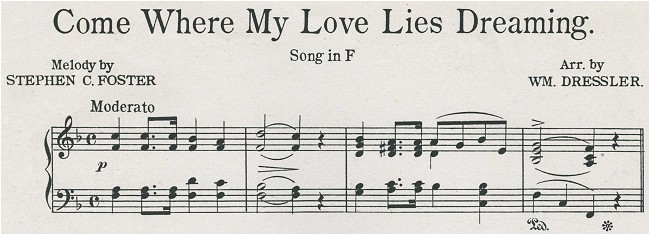

Duet, ‘Come where my love lies dreaming,’ Mr Palmer and friend.

There are murmurs of approval in the schoolroom at the sight of Moses Palmer preparing to deliver his third song this evening. Rightly so, as Mr Palmer’s musical talents are well known in north-east Shropshire – and not just as a singer.

Local papers show that Moses Palmer was conductor of the Oakengates Choral Society from the mid-1850s (Newport & Market Drayton Advertiser, 1 June 1855; Shrewsbury Chronicle, 2 November 1855), provided guidance to St George’s Choral Society when it was formed in 1859 (Wellington Journal, 7 May 1859; Eddowes’s Shrewsbury Journal, 11 May 1859), and played a leading part in the formation of the Coalpit Bank Choral Society the following year (Shrewsbury Chronicle, 9 March 1860).

Several of the concerts put on by those choral societies with Moses Palmer’s involvement were for charitable purposes. I think it’s quite likely that Mr Palmer is here tonight because the man for whom money is being raised by this event, John Preece, lives in the same part of Shropshire.

A hush is now descending, and the performance is beginning; here are the words (from The Guiding Star Songster ⇗, published a couple of years ago in 1865) if you’d like to follow along. If you haven’t jumped back in time with me to witness this live performance, I’ve also found an audio recording of a much later rendition, which although delivered by different artists (and a larger number of them) will give you a good idea of what we’re listening to, here in 1867.

Come where my love lies dreaming,

Dreaming the happy hours away,

In visions bright redeeming

The fleeting joys of day;

Dreaming the happy hours,

Dreaming the happy hours away,

Come where my love lies dreaming,

Is sweetly dreaming the happy hours away.

Come where my love lies dreaming,

Is sweetly dreaming, her beauty beaming;

Come where my love lies dreaming,

Is sweetly dreaming the happy hours away.

Come with a lute, come with a lay,

My own love is sweetly dreaming, her beauty beaming;

Come where my love lies dreaming,

Is sweetly dreaming the happy hours away.

Soft is her slumber, thoughts bright and free

Dance through her dreams like gushing melody;

Light is her young heart, light may it be,

Come where my love lies dreaming,

Dreaming the happy hours,

Dreaming the happy hours away;

Come where my love lies dreaming,

Is sweetly dreaming the happy hours away.

Intermission…

Time travel does not always go smoothly, unfortunately –sometimes it’s as if we lose our internet connection during an online presentation and then we’re ‘back in the room’. I’m not really au fait with the mechanics behind at all, but it might be a problem with the flux capacitor, or a random burst of chroniton particles causing a kind of ‘time burp’, or maybe even eddies in the space-time continuum ⇗. Whatever the cause, in being whipped out of time and then plonked back exactly where, but not exactly when we were, we have missed four performances.

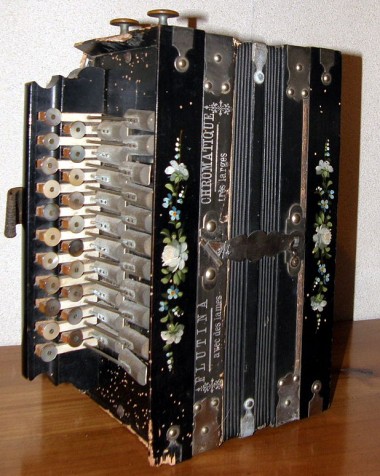

The newspaper report of this evening’s event gives us some idea of what happened in our absence, but some elements remain a mystery. “Beatrice (pianoforte and organ flutina), Miss Titley and Mr T. Hughes.” What was performed here? Quite possibly it was an air from the tragic opera Beatrice di Tenda ⇗. Mr T Hughes was presumably not the Mr Hughes we have already heard from (and who performed the next number). Miss Titley may have been one of Waters Upton’s own, Mary Jane Titley, daughter of Thomas Titley, a butcher, and his wife Elizabeth, née Icke. If so she was, like Miss Shakeshaft who we met earlier, another young performer.

“Song, ‘The Village Blacksmith,’ Mr. Hughes.” What a shame we missed this! The words of the song can however be found woven into my article Blacksmiths in Waters Upton. And you can listen to a more recent performance of it on YouTube. Next came “Song, ‘Poor old Joe,’ Mr. Palmer.” Now, this is a ‘plantation song’ and as such, contains terminology which isn’t acceptable in the 21st century, so I’m going to skip past it.

“Grand valse, Miss S. J .Shakeshaft.” This might have been one of any number of tunes with ‘Grand Valse’ in their titles, played on the pianoforte – possibly René Favarger’s Grande Valse de Salon, published in 1860. The performer I’m much more certain about: Sarah Jane Shakeshaft of Cold Hatton, daughter of farmer Joseph Shakeshaft and his wife Martha, née Wright. She must be about 18 right now, and I think that’s her over there looking suitably pleased having acquitted herself well in what was probably her first performance in front such an audience. In 1871 she will marry engineer Harry Gordon Collins and go to live with him at Handsworth in Staffordshire, but she will return to this neighbourhood after the untimely death of her husband in 1880. The 1881 census will show her, along with her two surviving children, living with her brother and sister-in-law John and Elizabeth Shakeshaft at Waters Upton.

Anyway, we are now back in the schoolroom, and the next song is about to be delivered.

Song, ‘A Motto for Every Man,’ a Friend.

The vocalist here is, I think, one of the friends brought over by Moses Palmer. The song was written by Harry Clifton (pictured below) and is also known as “Put Your Shoulder to the Wheel.” Once again, I’ve found the words – in Songs for English Workmen to Sing ⇗, published this very year (1867)! Plus, in case the words alone make the song sound rather dull, there’s a fabulous recording of it being sung by Stanley Holloway.

Some people you’ve met in your time, no doubt,

Who never look happy or gay:

I’ll tell you the way to get jolly and stout,

If you will listen awhile to my lay.

I’ve come here to tell you a bit of my mind,

And please with the same if I can:

Advice in my song you will certainly find,

And “a motto for every man.”

Chorus.

So we will sing, and banish melancholy;

Trouble may come, we’ll do the best we can

To drive care away, for grieving is a folly;

“Put your shoulder to the wheel,” is “a motto for every man.”

We cannot all fight in this “battle of life,”

The weak must go to the wall,

So do to each other the thing that is right,

For there’s room in this world for us all.

“Credit refuse,” if you’ve “money to pay,”

You’ll find it the wiser plan;

“And a penny lay by for a rainy day,”

Is “a motto for every man.”

A coward gives in at the first repulse;

A brave man struggles again,

With a resolute eye, and a bounding pulse,

To battle his way amongst men;

For he knows he has one chance in his time

To better himself if he can;

“So make your hay while the sun doth shine!”

That’s “a motto for every man.”

Economy study, but don’t be mean:

A penny may lose a pound:

Through this world a conscience clean

Will carry you safe and sound.

It’s all very well to be free, I will own,

To do a good turn when you can;

But “charity always commences at home,”—

That’s “a motto for every man.”

To be continued.

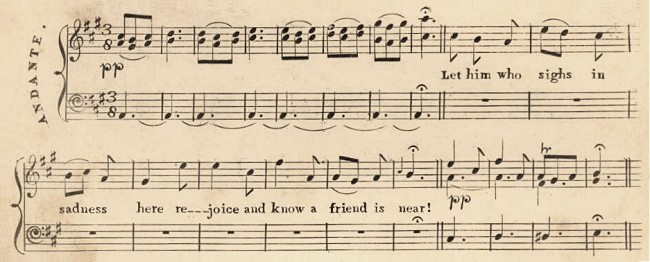

Picture credits. Extract from sheet music for Come Where My Love Lies Dreaming: Image from University of Texas Arlington Libraries ⇗ website, and used under a Creative Commons licence ⇗. The Village Blacksmith, sheet music cover: Public domain image from Picryl ⇗. Harry Clifton (1863): Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons ⇗.