⇐ Back to Part 1

I have little doubt that Dorothy Tudge was one of the first Shropshire women to volunteer for the Women’s Land Army. Pinning down exactly when she became a ‘Land Girl’ is tricky though, given that the date is not shown on her WLA index card. Also, that card recorded Dorothy’s age as 29, which if accurate (hint: I’m pretty sure it wasn’t!) would mean that she joined in 1936, well before pre-WW2 recruitment had started.

There’s a little more to be gleaned from that index card. Dorothy’s WLA number was 3872, and her address was her family home: Whittingslow, Marshbrook, Shropshire. Her occupation when she joined was ‘Poultry worker’; her qualifications were “6 years practical experience in poultry work, specializing in laying battery work.” Evidently she had moved on from the dairy work she trained for in the mid-1920s.

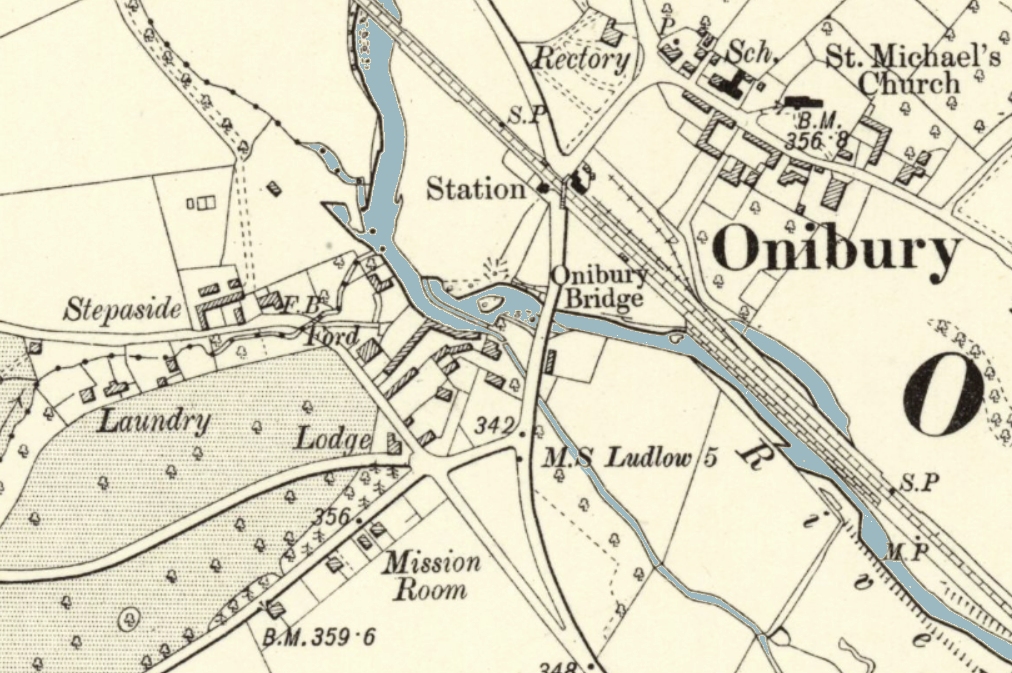

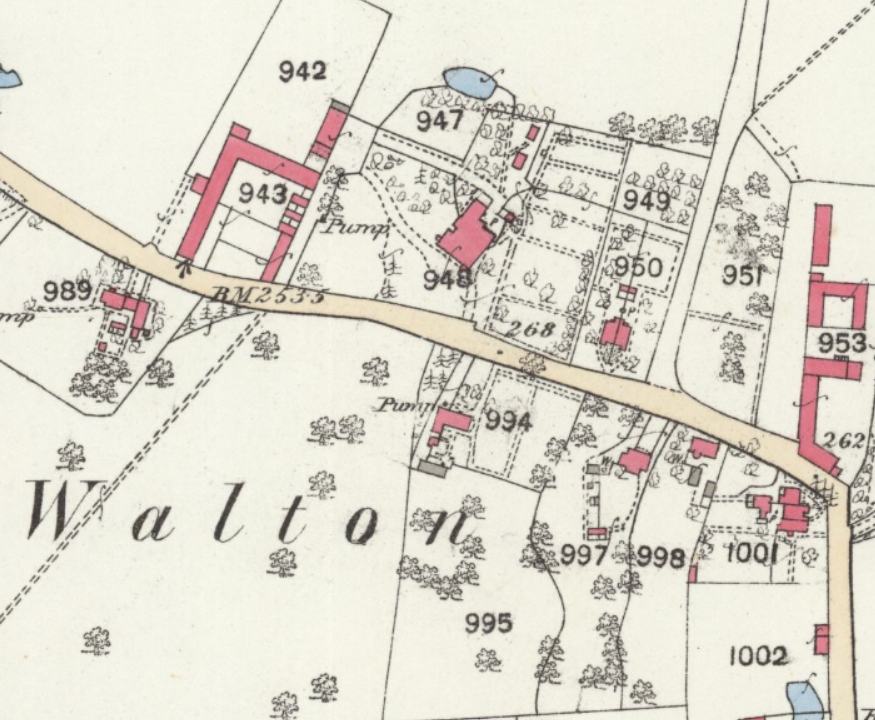

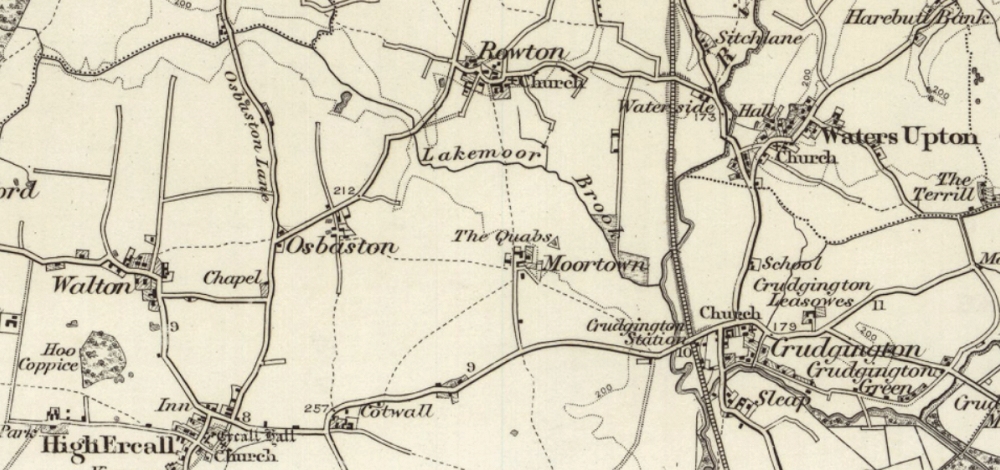

Waters Upton

Dorothy expressed a preference for ‘mobile’ rather than local service, and she was duly placed on a farm at the other end of the county; her stint as a poultry worker at Waters Upton was most likely her first ‘posting.’ She was recorded on the National Identity Register on 30 September 1939 at The Grange, where she lived with 70-year-old widow Edith Moore and Edith’s daughter Eileen.

This type of accommodation for Land Girls ⇗ was known as private billets. Treatment of WLA ‘guests’ in such billets varied – I hope Dorothy’s experience was towards the ‘one of the family’ end of the scale. I suspect that her farming background would have counted very much in her favour.

While part of me wonders about the specifics of what her poultry work involved, another part of me wants to know how Dorothy spent her time when she was wasn’t working. Did she explore the local countryside? Take walks into the village to visit the shop or post letters, engaging in cheery exchanges of greetings or conversation along the way? Take part in evening social functions in the old school room (though these seem to have mainly taken the form of whist drives!)? She would almost certainly have accompanied Mrs Moore and her family to church services on Sundays.

I’ll write in more detail about the Moore family at a later date. Suffice to say for now that the 1934 Kelly’s Directory showed Edith’s husband Robert Edward Moore, farmer, at the Grange Farm; he died in 1935 and the 1937 Kelly’s Directory lists his son Robert Henry Moore in his stead. From the 1939 Register we can see that Edith continued living at The Grange, while her son Robert was based, with his wife and children, at The Grange Cottage (a little further down Catsbritch Lane). Robert was described in the Register as a ‘Mixed Farmer.’ I suspect that he did not have a poultry unit himself – I think it more likely that a tenant renting one of his cottages did, on a piece of land that went with the cottage.

There were three cottages, and nearly 190 acres of land, attached to The Grange Farm. All of this property was sold in September 1941 when the Moores moved on from Waters Upton. Perhaps that was when Dorothy departed too.

Much Wenlock, then Whittingslow once more

By July 1942, Dorothy was based on the other side of Wellington from Waters Upton, at Bradley Farm, just North of Much Wenlock. I know this because of a lengthy report in the Shrewsbury Chronicle of 23 October 1942 (page 8) headlined “Petrol Rationing Offences.” Miss Constance Jean Conroy was at the centre of this case, as the person who illegally received and used petrol coupons; she was fined £40 in respect of eight offences. Dorothy Tudge, one of the parties who had transferred coupons to Miss Conroy, was fined a grand total of £1!

Meanwhile, other members of the Tudge family were also involved in the war effort. Dorothy’s father William was a Lieutenant in the Whittingslow Home Guard Platoon (Shrewsbury Chronicle, Fri 21 May 1943, page 4). Her brother Herbert meanwhile had joined the RAF. His active service was sadly short-lived…

While confirmation that Herbert was a prisoner of war was good news considering the alternative, this meant that he spent most of the war in Stalag Luft III. The Shrewsbury Chronicle of 22 December 1944 (page 5) conveyed the news that Herbert’s parents had received a photo showed Herbert and other officers taking part in a play staged at the prison camp, “Blithe Spirit,” in which Herbert played a female part. A copy of the photo appeared in the paper’s edition of 12 January 1945 (page 6).

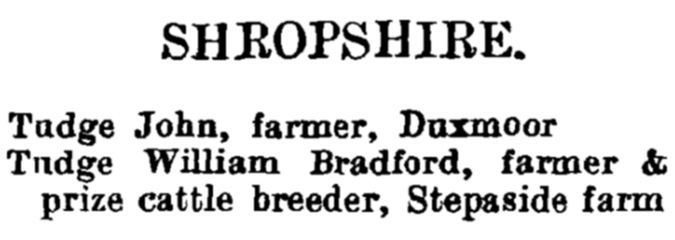

Notices in the Shropshire press towards the end of 1944 suggest that Dorothy Tudge was by then back on ‘home turf’ and had, along with her cousin Helen Maybery, turned her hand to rearing pigs. Those notices (including one on the front page of the Shrewsbury Chronicle of 13 Oct 1944) related to the annual sale of pedigree and commercial pigs at Shrewsbury, scheduled for 27 October. Those entering animals to the sale included “Misses Tudge and Maybery, Marshbrook (Large Blacks)”. After that, news on Dorothy’s whereabouts and activities is hard to find for a while. Let’s return to her obituary to pick up the latter part of her story.

Wadhurst

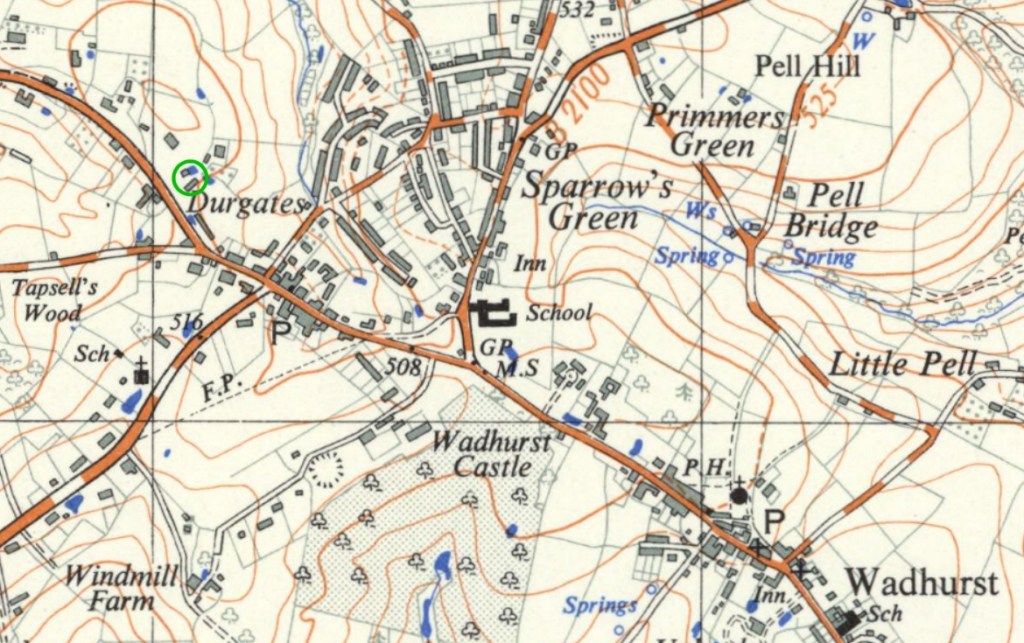

Dorothy’s father William Tudge went to Wadhurst too. He was included in the household at Great Durgates Farm on the 1955 electoral register for the East Grinstead Constituency. Sadly, he had died by the time the register came into force in February that year. The Wadhurst burial register shows that he was buried at the parish church on 10 December 1954.

Dorothy, as her obituary shows, became an active member of the local community she had joined. I have not found any information about the ‘other local activities’ she supported, or which charities she worked for. Her involvement with the local Women’s Institute, however, can be tracked – in part – via newspaper reports.

The earliest such report that I’ve discovered dates from June 1965, when Dorothy was one of three WI members who got full marks in the competition “My prettiest piece of china” (Kent & Sussex Courier, 4 June, page 16). Dorothy is recorded as Treasurer in 1969 (same title, 21 February, page 13), and in 1973 her efforts to collect information and photographs relating to the early years of Wadhurst WI were publicised (same title, 1 June, page 2, and Sussex Express, 5 October, page 20). The final snippet that I’ll share appeared in the Sussex Express, 30 December 1976, page 26:

Dorothy’s obituary in The Courier concluded by noting that her funeral took place on 13 December 1976, at Tidewell. Her mother, after dying at the age of 97, joined her there in 1982.

A gravestone in Tidewell churchyard marks the spot where the former Land Girl of Waters Upton and her Mum lie together in eternal and well deserved rest.