⇐ Back to Part 1

As we have seen, when the Cold Hatton Association was formed in 1769, drawing members from several small settlements including Waters Upton, it aimed “to prosecute all Felons, especially Horse-stealers”. In the years that followed, while horse thieves remained a priority, the Association (hereinafter referred to as the CHA) developed and diversified its mission, with the deterrence of other forms of felony falling more firmly within its remit.

There was a lot of variation in the notices published by the CHA in its early years, as the young organisation sought to define who, and what, it was for. There was also the matter of how best to present itself to the public, or at least that section of the public who either read the newspapers or had the papers’ news and notices conveyed to them. Within that part of the populace were potential new members, potential partners in crime-fighting, and quite probably some of the felons who might see themselves as potential defendants should they be collared by the CHA.

The CHA was not alone in this experimental phase of its existence, as I have seen the same variation in the notices published by similar Salopian societies around this time. I think there was a lot of ‘borrowing’ of ideas, with the various prosecution associations taking note of (and taking some of the wording from) what the others had published in the papers.

In 1771, the CHA advertised that it was “a Society for Prosecuting House-breakers, Horse-stealers, and all other Kinds of Felony whatsoever.” 1773 saw a slightly more detailed agenda published. The CHA would “endeavour to apprehend and prosecute all Persons who shall be guilty of committing Felony or Larceny on the respective Properties” of it members, and it set out the actions to be taken by any member “who shall have his, her, or their House broken open, or Horse, Cattle, or other Property stolen”.

Hedge-tearers, and Springle-getters

The emphasis on equines returned in notices published from 1774 to the beginning of 1777. In September 1777 however, the following statement was added to the CHA’s notice: “They are also determined to prosecute all Hedge-tearers, and Springle-getters to sell, and others that cannot give Account of themselves.”

Hedge-tearers? George Roberts, in his 1856 publication The Social History of the People of the Southern Counties of England in Past Centuries ⇗, categorised hedge-tearers with wood-stealers, spoilers of hedges, “and to crown all, the pollers of trees.” These were poor folk who, in order to obtain fuel for their fires, would plunder the local woods and hedgerows (and presumably, in the case of wood-stealers, their wealthier neighbours’ wood piles). Roberts was writing about the late 1500s in Dorset and Somerset, but evidently hedge-tearers were also a problem two centuries later in Shropshire. Were the Salopian hedge-tearers of that time also looking for fuel, or were they simply vandals?

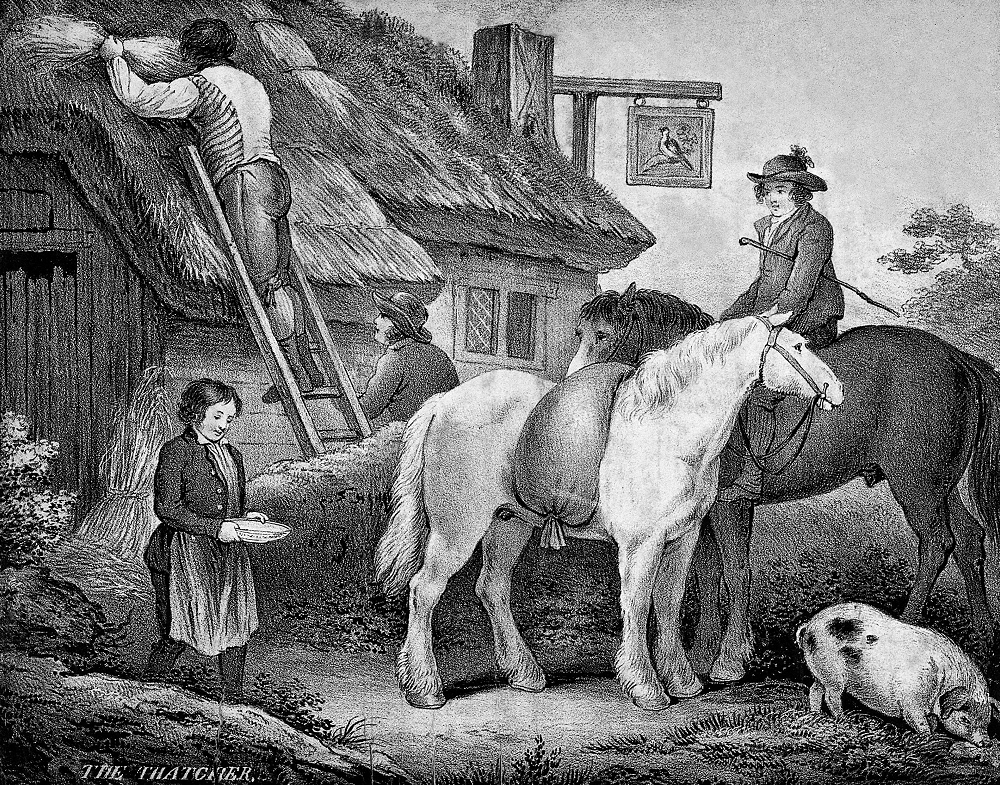

Springles could also have been a source of firewood, but were being stolen by ‘springle-getters’ so that they could be sold. In an 1894 issue of Notes and Queries ⇗, a correspondent stated that “’Thatching springles’ are willow or hazel rods four feet long, split and with the ends sharpened, and used to bind down the thatch.”

This was in reply to a query in an earlier issue, about the appearance of springles in the churchwardens’ accounts of High Ercall, the parish in which Cold Hatton lay and which Waters Upton was adjacent to. Springles were also mentioned in the eighteenth century accounts of the Overseers of the Poor, in the North Shropshire parish of Moreton Corbet. They were listed along with other items used in connection with “thetching” parishioners’ houses. I have an 1883 edition of the Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society ⇗ to thank for that snippet of information.

Clearly, the gentlemen freeholders and farmers of Waters Upton and nearby settlements valued their hedgerows, which helped to keep their cattle and other animals in the fields where they belonged. And it appears that a good number of people in that area had houses with thatched roofs.

All Manner of domestic Fowls; Posts, Rails, Styles, Gates, &c.

The 1777 statement regarding hedge-tearers and springle-getters was retained in a notice published in 1778. That notice was repeated more or less verbatim along with the ever-changing list of CHA members, through to 1781. It specified that members would “pursue and prosecute any Offender or Offenders that shall be guilty of any Felony or Larceny, on any of our respective Persons or Properties; more especially House-breakers, Horse-stealers, and Sheep-stealers”.

The list of offences which the CHA sought to deter through pursuit and prosecution increased in 1783, when the following notice appeared in Aris’s Birmingham Gazette:

In the years that followed, the content of the CHA’s notices broadly followed that of 1783, almost without exception (a horse-focused notice appeared in 1785). They typically began with the Association’s name, and an opening statement along the lines of: “WHEREAS several Burglaries, Felonies, Grand and Petit Larcenies, have frequently of late been committed in [the Townships covered by the Association]”.

In 1785 “Hooks and Thimbles” were added to the list of items which, if stolen, would attract the attention of the CHA. These were used in the hanging of gates, a subject I found way more information about than I expected in volume 1 of The Complete Farmer ⇗, published in 1807! According to The Dialect of Leicestershire ⇗, the thimble is the ring which receives the hook in the hinge of a gate.

The wording of the CHA’s notices became fixed from September 1795, with the notice being supplemented from 1799 by a list of rewards. (From 1801 it was clarified that the rewards were offered “on Conviction of Offenders”.)

The felonious burning any house, barn, or other building

The highest reward, of five guineas, was offered in respect of “The felonious breaking and entering any house in the night time” and also “The felonious burning any house, barn, or other building, or any rick, stack, mow, hovel, cock of corn, grain, straw, hay, or wood”. The next highest reward, of three guineas, was offered in respect of “The felonious stealing, killing, maiming, or wounding any horse, mare, or gelding” and in addition, for a new item: “Any servant unlawfully selling, bartering, giving away or embezzling any coal, lime, hay, or other his, her, or their master or mistresses property”.

Smaller rewards, down to a single guinea, were offered in respect of various other offences. Most of these we are familiar with from earlier CHA notices, but the term ‘hedge-tearers’ was abandoned. It was replaced, and combined with several related offences as “The breaking open, throwing down, leveling or destroying any hedges, gates, posts, stiles, pales, rails, or fences”. The range of crimes against crops falling with the CHA’s scope was also expanded, in “The stealing or destroying any fruit tree, root, shrub, plant, turnips, or potatoes, pease, &c. robbing any orchards or gardens”.

These notices, lists of rewards, and lists of members, continued to be published every year – with a few exceptions – up to 1812. The exceptions might be years in which, for whatever reason, the Association did not publish any notices. Or they might be the result of my failure to find search terms which would reveal them in the British Newspaper Archive’s collection!

From the CHA’s notices and lists of rewards, we gain insights regarding the lives of some of the people in Waters Upton and the surrounding area, who were members of the Association in the latter part of the 1700s and first decade or so of the 1800s. We see something of the livestock, crops and other property they owned, what was of value to them, and what was at risk of being stolen or damaged.

Who were the CHA members of Waters Upton though? We have seen their names (in Part 1), but what else is there we can learn about them? Were they all gentlemen and farmers? In Part 3 of this article I will begin my quest for answers to these questions. I will also look at what happened to the Cold Hatton Association for the Prosecution of Felons after 1812.

To be continued.