⇐ Back to Part 1 (A Man Missing)

It appears that Thomas Plant of Waters Upton originated from Mucklestone, a parish which back then included parts of both Shropshire and Staffordshire. The baptism of “Tho: Plant Son of John Plant & Eliz: his wife” took place on 18 September 1726 ⇗ (making Thomas just under 50 rather than “upwards of” that age at the beginning of 1776). Then, on 4 September 1750 ⇗ and also in Mucklestone, the wedding of “Thomas Plant & Ann Thomas both of this Parish by Banns” took place.

The Thomas Plant who was baptised in 1726 would have been 23 or maybe 24 years old when the above marriage took place, so I think the chances are good that he was the groom. What, though, are the odds that he was also the Thomas Plant who, with wife Ann, had children at Waters Upton a few years later and, later still, went a-wandering just before the snowfall of the century?

Another question: there was a gap of about five years between the marriage of Thomas Plant and Ann Thomas in 1750, and the first baptism of a child of Thomas and Ann Plant at Waters Upton in 1755 – were there any children born in that gap who might belong to this family?

In my attempt to answer the second question, I turned to Findmypast. This website has excellent collections of digitised and indexed parish registers from both Shropshire and Staffordshire (although oddly, while there are images of the register containing Thomas Plant’s baptism, that register has not been indexed). In addition, they have a very useful way for subscribers to search for vital events from across their record sets. This allows us to look for events falling within a range of distances from a particular place.

“Daughter[s] of Thomas & Ann Plant of Chetwyn Parish”

After using this search functionality I found myself focussing on two of the baptisms it revealed, both falling in the period from 1750 to 1755, and both at Hinstock (about seven miles away from Mucklestone, as the crow flies). First, on 6 Aug 1751 ⇗, there was Mary. Then, on 20 May 1753 ⇗, there was Elizabeth. Each of these girls was described in the parish register as being a “Daughter of Thomas & Ann Plant of Chetwyn Parish”.

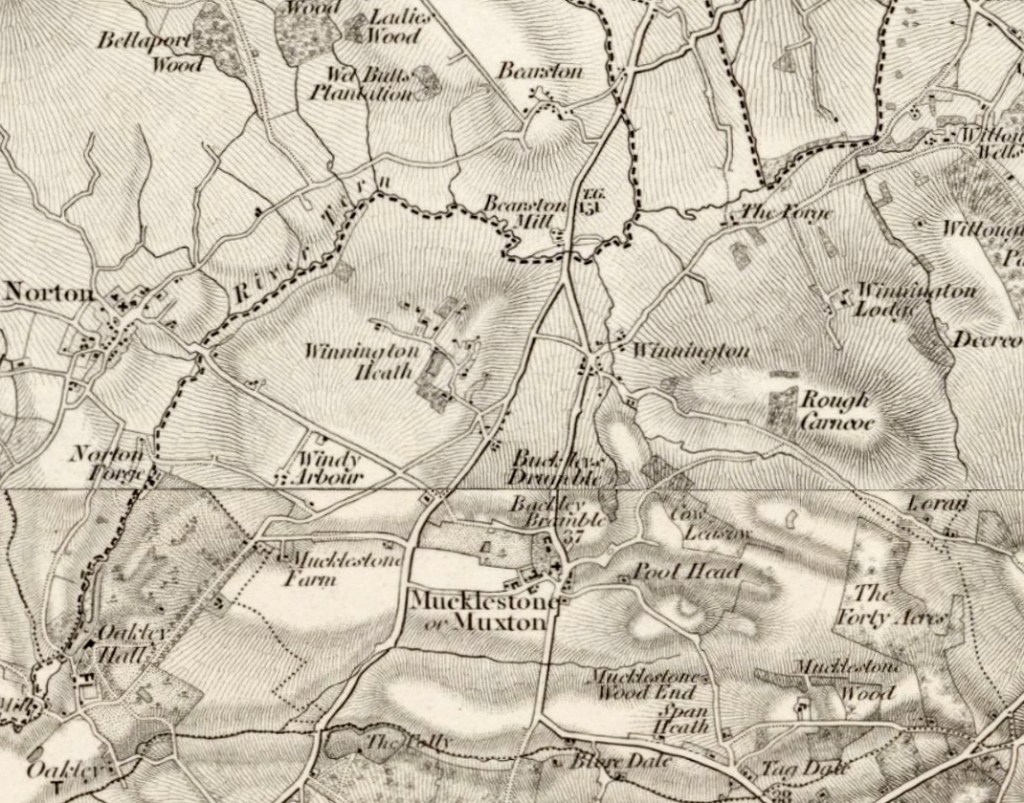

For ‘Chetwyn,’ by the way, read Chetwynd: the Plant family had probably, erm, planted themselves somewhere in the north of that parish, such as Sambrook. At that time Hinstock’s church would have been closer than the one in Chetwynd village (Sambrook St Luke ⇗, shown on the map below, was not built until 1856).

Depending on exactly where in the northern part of Chetwynd parish the Plants were living, the distance by road from their abode to Waters Upton might have been somewhere between six and eight miles, or thereabouts. Did the Plant family of Chetwynd travel those roads and become the Plant family of Waters Upton? After researching their children, I believe they did.

My attempts to find out what happened to the Plant children have met with mixed results. The fate of Thomas Plant junior was all too easy to determine. Turn over a leaf of the Waters Upton parish register, from the pages showing his baptism in 1759, and you find the burial of the same “Thomas Plant the Son of Thomas and Ann Plant”. He was laid to rest on 11 August 1761, his second birthday having been his last. As for the sisters of this unfortunate boy, I’ll look at them in order, from the youngest to the eldest.

Margaret Plant was baptised in the month following her brother Thomas’s burial. It appears that she may have married in her home parish – at the age of 42. Banns of marriage between “Thomas Groom of the Parish of Bolas, Bachelor, & Margaret Plant of this Parish, Spinster” were published on three successive Sundays, May 1, 8 and 15, prior to the nuptials at Waters Upton on Monday 16 May 1803.

I have looked for baptism records for any children who may have been born of this union, in case the bride was another, younger Margaret Plant, but have found none. Neither, sadly, have I found death or burial records that I can link with any certainty to Thomas or Margaret, confirming their ages.

Even more speculative are my conclusions regarding Martha Plant. She may have married Edward Podmore at Chetwynd on 29 December 1781 ⇗. If she did, she might have ended her days in that parish: Martha Podmore of Chetwynd End, age 70, was buried at Chetwynd on 6 December 1824 ⇗.

“Elisabeth, the base-born Daughter of Ann Plant”

For Ann, there is another entry in the Waters Upton parish register besides her baptism which almost certainly relates to her – and to her daughter. On 7 March 1776 “Elisabeth, the base-born Daughter of Ann Plant by Edward Jones of Kidderminster” was baptised.

I am not at all certain what happened to baby Elizabeth, although I hope she survived, thrived, and was supported financially by the man who fathered her out of wedlock. I don’t think Ann married Edward Jones. She may have been the Ann Plant who wed a man whose name has been transcribed as John Esbury, at Stoke Upon Tern on 23 June 1778 ⇗.

Further guesswork is all that I can offer in the case of Ann’s sister Elizabeth Plant. She was possibly the bride of Thomas Talbot, in a marriage solemnised at Church Aston on 28 December 1776 ⇗. She might then have been the widowed Elizabeth Talbot of Chetwynd Heath who was buried 6 April 1783 ⇗ at Chetwynd.

For the firstborn child of Thomas and Ann Plant I believe I can offer greater certainty. Following the publication on 20 and 27 November and 4 December 1774 of Banns between “Thomas Cartledge and Mary Plant both of this Parish”, that couple were married at Waters Upton shortly afterwards on 15 December. Both parties made their marks rather than signing the register. One of the witnesses who likewise made her mark was Ann Plant, who was likely to have been either the mother or the younger sister of the bride.

Mary, you might remember, was one of the two Plant girls baptised at Hinstock. This marriage, I think, confirms her (and her sister Elizabeth) as part of the Plant family of Waters Upton. In which parish Thomas and Mary Cartledge remained after their wedding. Five children, Sarah, Mary, John, Elizabeth and Thomas, were born to this couple, all baptised in the church of St Michael in the latter half of the 1770s and the early 1780s, the surname in each case written as Cartlidge.

“Thos. Plant a Pauper”

Let’s return to the parents of these children, Thomas and Ann. There are burials for both of them in the Waters Upton register. “Ann, the Wife of Thomas Plant, aged 62” was interred on 9 May 1780. Despite the slight age discrepancy, I think that makes her “Ann ye daughter of John Thomas of [probably Napley – part of the page is missing] Laborour”, baptised 30 January 1720/21 ⇗ at Muckleton.

Notice that the register entry for Ann’s burial refers to her as the wife, not the widow, of Thomas Plant. Thomas did survive the spectacular snowfall of January 1766, and at some point he did return to Waters Upton. His burial, on 27 December 1785, was entered in the parish register as “Thos. Plant a Pauper, aged”. Possibly the clerk meant that Thomas was aged as in old, but more likely I think is that Thomas’s age was never ascertained and the register entry was left incomplete.

Wait though – Thomas, a farmer in 1776, was a pauper at the time of his death? This is entirely possible. He may have been what we would now call a smallholder, renting and cultivating (and/or grazing livestock on) a relatively small acreage. And he may have suffered a setback, in the form of crop failure, diseased livestock, or personal ill-health for example, which left him unable to keep the farm and support himself in his later years.

Perhaps Thomas’s trip to Staffordshire (or wherever he actually went!), followed by his failure to return home for a couple of months or more, was the first sign that things were not well with him, with his farm, or with his finances. In which case, a cynic might take the view that Thomas’s ‘afflicted friends’ were actually creditors trying to track down the man who owed them money.

I prefer to believe that Thomas had friends who genuinely cared about him. Friends within his local community who were so concerned by his disappearance in the dreadful winter weather of January 1776, that they were prepared to pay for notices in newspapers in the hope of finding him alive and reuniting him with his family. Thomas Plant, the blue-suited ‘stout made man’ of Waters Upton, may have ended his days financially impoverished, but well off in that priceless commodity known as friendship.