So began a report in the Wellington Journal on Saturday 14 September 1889 (page 7) – a report so long that I have only included the above paragraph in this website’s Education in the news page. More of the article deserves to be seen however, and commented on: hence this post.

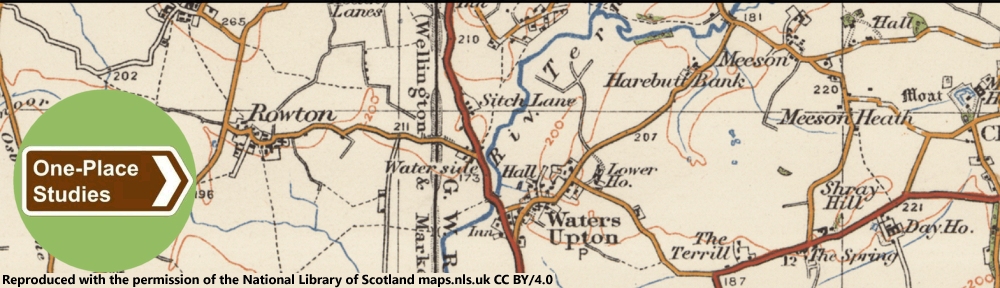

There are two things about the news story that are of particular interest to me. Firstly, it looks back at, and provides an insight into, the foundation of Waters Upton’s school. Since I have failed to find much newspaper coverage from the time when the school was proposed, built, and opened, this is valuable information. Along with this information there are also opinions about education provided – or rather, not provided – in Waters Upton before the school existed.

Secondly, the support that was needed for Waters Upton to establish its school (and then to expand and maintain it) becomes apparent. A community that extended well beyond the boundaries of this small parish was essential for success.

Let’s continue with the Journal’s report, and set the scene…

“a strikingly ornate appearance”

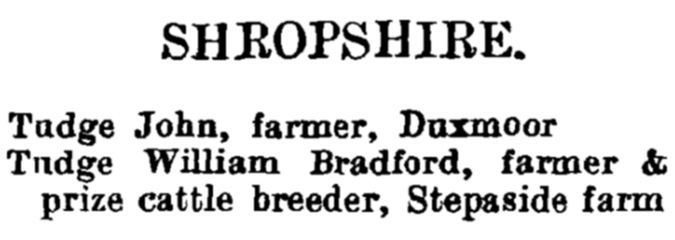

As the article continues, some idea of the extent of the support network enjoyed by Waters Upton becomes clear. Some of the people named were residents of the parish, and some were the neighbouring parishes of Ercall Magna and Bolas Magna (a few of them may be familiar if you have read Late Victorian Christmases in Waters Upton). Many however were from further afield…

“20 years ago […] there was no school in the parish”

With the scene set, and the supporting cast introduced, the Reverend John Bayley Davies takes centre stage. The indefatigable rector was, I believe, the driving force behind the establishment, and the success, of Waters Upton’s school. He was soon talking about the subjects that I have expressed interest in…

There are a few things to unpack from the above, especially the second paragraph. First of all, was there really no school in the parish back in 1869? That depends on how you define ‘school.’ It is certainly true that at the time in question, there was no educational establishment in Waters Upton receiving Government funding and inspection.

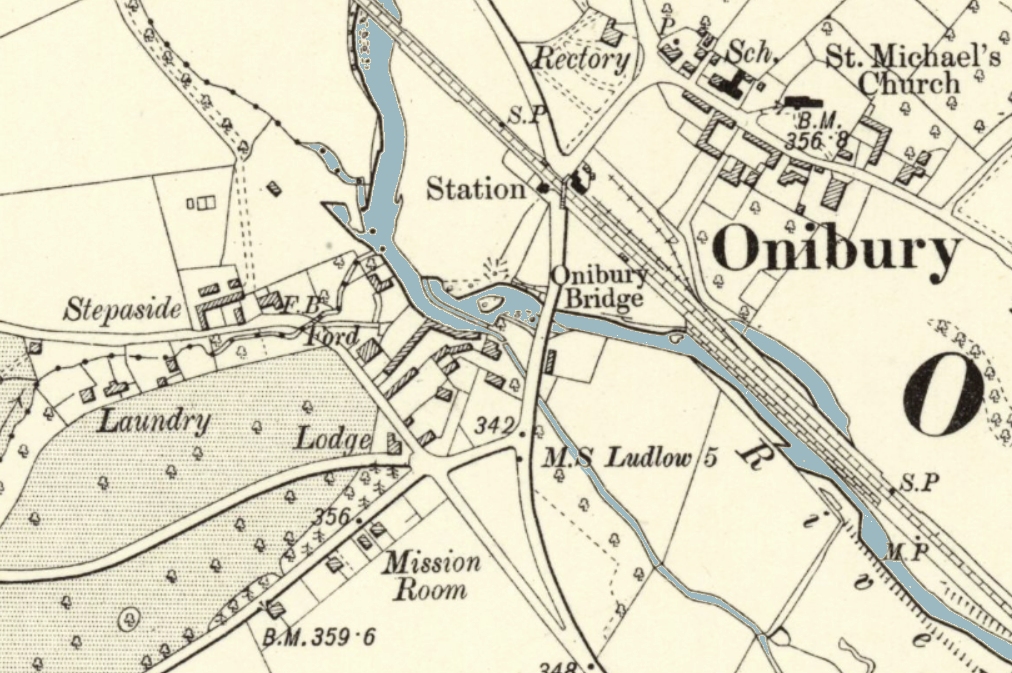

Yet, if you look at the census returns for Waters Upton up to 1871 (and at other sources for the years before the 1841 census) there were teachers in the parish. Most, I believe, were teaching in what were termed ‘dame schools.’ The establishment run by Mrs Anne Walker (assisted by her daughter Sarah by the time of the 1871 census) was probably a step up from the others, and survived well beyond the opening of the village school. Several of Rev Davies’ predecessors also took in boarding pupils, for a fee, at the rectory.

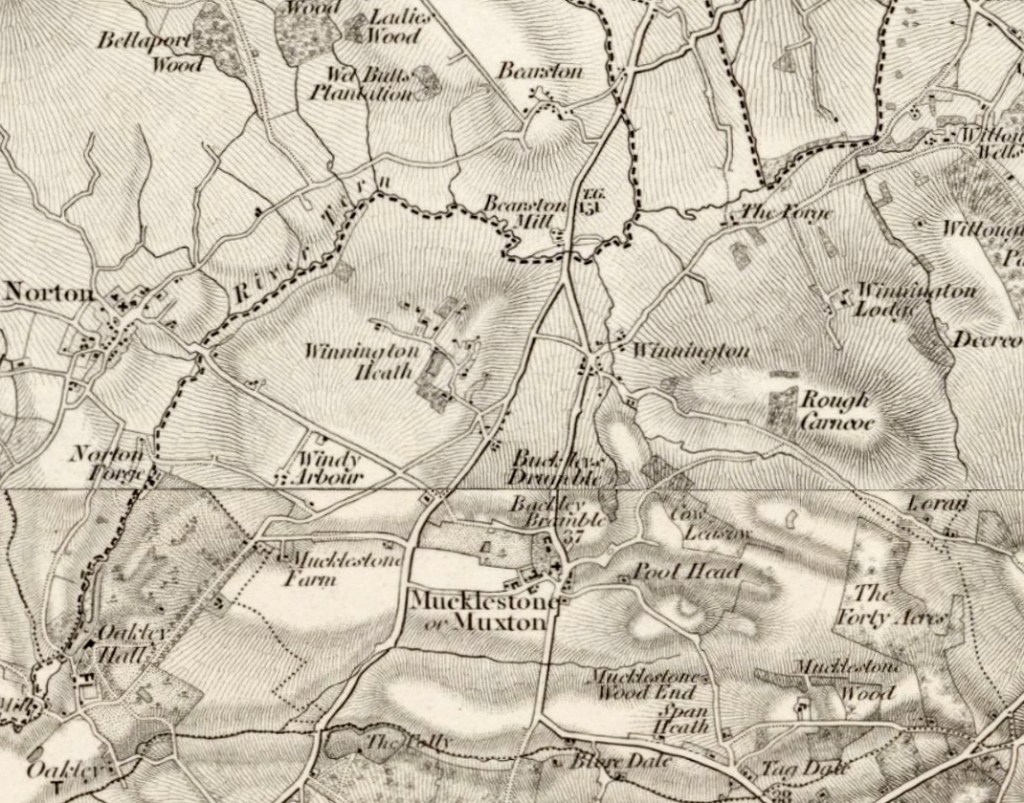

So, there were certainly places within the parish where children could be taught – and if we look just a little beyond the parish boundary there were at least a couple more educational facilities that some from Waters Upton might have attended.

I will write in more detail about these various schools and teachers at another time; for now I will just say that the Rev Davies probably had good grounds for fearing “that many the children grew up very imperfectly educated”! And the rector was absolutely right to say that the Education Act of 1870 ⇗ “put them all upon their mettle”. Under that Act, in 1873 the Education Department issued a notice that galvanised Rev Davies, and his supporters within and beyond the parish, into action.

“Some difficulty was experienced in providing a school”

That notice basically gave the residents of Waters Upton, Cold Hatton and neighbourhood an ultimatum. In a nutshell it said: A school for 100 children is needed in your area. If one is not provided voluntarily (for example, a ‘National School’ like the many others already established elsewhere by the Church of England) a ‘Board School’ (non-denominational, managed by an elected board, and paid for in part from the rates) will be established. A ‘voluntary’ school, tied to the Church, which would receive Government grants (and inspections) but not impose upon the ratepayers, was seen as the way to go. This took some determination. A lot of help was required – and was readily given…

John Bayley Davies then mentioned the bazaar held in 1876 to clear the initial debt on the newly-built school, and praised the “excellent teacher” then in place (Amelia “Minnie” Amos, who would soon be leaving – her story, and those of the other teachers at the school, will be told in due course).

After the conclusion of Rev Davies’ speech the sale of work was formally opened: “Lady Mabel Kenyon-Slaney came forward amid considerable applause, and in a few neatly-chosen words, declared the sale open, and wished the promoters every success.” (This was followed by many more words from her husband, Colonel William Kenyon-Slaney, the local MP.)

According to the Wellington Journal, “Business was then briskly proceeded with, the ladies using their proverbially persuasive powers with highly satisfactory results.” Including donations, £89 18s. 8d was raised over the two days of the sale. If you would like me to share the details, by reproducing the rest of the newspaper article, leave a comment and I will add a Part 2 to this post!